Last updated:

‘Military exemption courts in 1916: a public hearing of private lives’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jennifer McNeice

Amid ANZAC commemorations and stories about the eagerness of Australian men to join World War I, it is rarely reported that approximately 45% of eligible men did not enlist and more than 87,000 men actively sought exemption from military service. Acknowledging these statistics, and the experience of these men, does not diminish respect for those who served or for the sacrifices they made. Instead, it allows a more accurate perspective from which to view their actions. This article explains the historical context of exemption court records and explores how these records can help illuminate the experience of the men who stayed at home. Those seeking a deeper understanding of the social context of military service can consult exemption court records that are freely available at Public Record Office Victoria. The records document men who sought exemption from military service, their reasons for doing so and the decisions of the exemption courts.

Voluntary recruitment

The enthusiasm of Australian men to volunteer for service in World War I is legendary. Young men pretended to be older and old men pretended to be younger. Others, dismayed by rejection, tried to enlist at different locations. These truths are embedded in the Australian public consciousness. But another truth, affecting more men, is less well known. The narrative has tended to ignore the men who chose not to volunteer.

As we shall see later in this article, some of these men actively sought exemption from military service. Exemption court records at Public Record Office Victoria document the reasons the men gave in their applications for exemption. Together with newspaper reports of court proceedings, they provide a broader and more balanced perspective about the government’s campaign to encourage men to enlist.

Australia entered the war in the midst of a general election following a double dissolution of the federal parliament. Both sides pledged support for the war, with Labor’s Andrew Fisher declaring that Australia would be in it ‘to the last man and the last shilling’ before winning a majority in both houses on 5 September 1914.

Ultimately there were 416,809 enlistments in the army during the war. This number represents 38.7% of the eligible male population, that is, men between 18 and 44 years of age.[1] It is estimated that a further 178,800 were rejected.[2] Therefore approximately 45% of eligible men did not try to enlist.

|

Enlistment status |

Approximate % of eligible males |

|

Did enlist |

38.7% |

|

Tried to enlist but rejected |

16.6% |

|

Did not try to enlist |

44.7% |

Table 1: Voluntary recruitment of eligible population

Under section 49 of the Defence Act 1903, soldiers could not be conscripted to serve beyond the limits of the Commonwealth of Australia, so a volunteer force was required. There was no difficulty in obtaining the enlistments required to fulfil Australia’s initial promise of 20,000 men. But as the war continued, enlistments fell and the demand for new forces and reinforcements increased.

|

Month |

1914 |

1915 |

1916 |

1917 |

1918 |

|

January |

10,225 |

22,101 |

4,575 |

2,344 |

|

|

February |

8,370 |

18,508 |

4,924 |

1,918 |

|

|

March |

8,913 |

15,597 |

4,989 |

1,518 |

|

|

April |

6,250 |

9,876 |

4,646 |

2,781 |

|

|

May |

10,526 |

10,656 |

4,576 |

4,888 |

|

|

June |

12,505 |

6,582 |

3,679 |

2,540 |

|

|

July |

36,575 |

6,170 |

4,155 |

2,741 |

|

|

August |

25,714 |

6,345 |

3,274 |

2,959 |

|

|

September |

16,571 |

9,325 |

2,460 |

2,451 |

|

|

October |

9,914 |

11,520 |

2,761 |

3,619 |

|

|

November |

11,230 |

5,055 |

2,815 |

1,124 |

|

|

December |

9,119 |

2,617 |

2,247 |

||

|

Total |

52, 561 |

165,912 |

124,352 |

45,101 |

28,883 |

Table 2: Enlistments by month (except 1914 which is given as an aggregate covering August to December in that year). Source: E Scott, Official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, Volume XI, Australia during the war, seventh edition, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941, pp. 871–72.

The War Precautions Act 1914, enlarged eligibility criteria, recruitment drives, a war census and attempts to introduce full conscription were among the techniques used to try to boost enlistments.

As the number of recruits dwindled, the eligibility criteria expanded. In the first year of the war the upper age limit of recruits was increased from 35 to 45 years; the minimum chest measurement was reduced from 34 inches to 33 inches; and the minimum height of 5 feet 6 inches was reduced to 5 feet 2 inches. In April 1917, the height standard was reduced again to 5 feet.[3]

War census and call to arms

The War Census Act was given Royal Assent on 23 July 1915, and subsequently, a war census was taken between 6 and 15 September. All males aged between 18 and 60 years of age were required to complete the first schedule, that is, the personal card, and everyone 18 years of age and over who possessed property or income had to complete the second schedule, that is, the wealth and income card.

The personal card asked questions about name, address, age, marital status, dependants, health, occupation, military training, possession of firearms and ammunition, place of birth, parents’ places of birth and naturalisation.

In June 1915 Australia pledged 5,300 men each month as reinforcements.[4] Reports from Gallipoli and intense recruiting drives saw a spike in enlistments through July and August of the same year. By November, data from the war census showed that Australia still had almost 600,000 fit men between 18 and 44 years of age.[5] It was reported that the number required for reinforcements had grown to 9,500 each month and William Hughes, who had replaced Fisher as Prime Minister, announced that an additional 50,000 men were needed before June 1916.[6]

|

Description |

Number |

|

Males 18–34 of neither enemy birthplace nor enemy parentage |

661,544 |

|

Males 35–44 of neither enemy birthplace nor enemy parentage |

293,774 |

|

Males 18–34 of enemy parentage but not enemy birthplace |

19,597 |

|

Males 35–44 of enemy parentage but not enemy birthplace |

10,562 |

|

Males 18–34 of enemy birthplace |

6,547 |

|

Males 35–44 of enemy birthplace |

3,848 |

Table 3: Enemy origin of males 18–44 years of age identified in war census. Source: GH Knibbs, The private wealth of Australia and its growth together with a report of the war census of 1915, Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, Melbourne, 1918, p. 15.

The war census recorded details of 1,349,597 men between 18 and 59 years of age and identified approximately 990,000 men between the ages of 18 and 45, other than enemy subjects.[7] In December 1915, regulations under the War Precautions Act required these men to answer more questions including:

Are you willing to Enlist Now? Reply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

If you reply ‘Yes’ you will be given a fortnight’s notice before being called up.

If not willing to enlist now, are you willing to enlist at a later date? Reply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, and if willing, state when.

If not willing to enlist, state the reasons why, as explicitly as possible.

A special appeal from Prime Minister Hughes, the ‘call to arms’, was enclosed with the form. Hughes claimed that 16,000 men were needed each month for reinforcements, in contrast with the figure of 9,500 men reported the previous month.

Some expressed the view that ‘there is a veiled threat about this manner of appealing for volunteers’.[8] Eligible men who had not signed up would have felt considerable pressure. The number of recruits spiked again but many men remained defiant. In May 1916 Senator Millen reported that the census showed 120,000 single men of military age were not willing to enlist.[9]

It was an issue that had the potential to divide communities, or perhaps bring underlying divisions to the surface. The 1916 Irish Easter Rising and subsequent executions added to the tension. The widow of one of the Irish rebels, Skeffington, reported, ‘My husband was unarmed, he was a non-combatant, and he was an earnest and a well-known pacifist. I was not allowed to see my husband, to receive a message from him, or to bury his body.’[10] Such testimony would produce sympathy even from those who initially deplored the rebels’ actions. ‘Many ordinary Catholics, coming from the working classes, would not have supported conscription anyway, and British repression in Ireland only strengthened their opposition.’[11]

Conscription plebiscite and call up

The massive loss of lives at Pozieres in July 1916 put further strain on the volunteer system. Hughes called for a conscription plebiscite. The Referendum Bill was announced on 14 September: Australia would vote on conscription on 28 October 1916. What happened in the interim probably influenced the result.

The Defence Act already allowed men between 18 and 60 years of age to be called up for service within Australia. Hughes assumed that Australians would vote in favour of conscription and he wanted men in training camps quickly so that overseas conscription could be implemented soon after the referendum. A proclamation on 29 September 1916 required single men between 21 and 35 years of age to report for medical examination. It is not clear how many men were obliged to comply with the call up, due to the delay since the time the census was taken and changes in categories. The following excerpt gives some idea of the difficulties:

Senator Pearce in reply to Senator Barnes (Vic.) said that 230,000 fit, single men between 21 and 45 were registered when the census was taken. The fit single men at the time of the census, between 18 and 45, numbered 307,150. Of those 103,748 had enlisted and embarked up to June 9, 1916, and 50,492 had enlisted and were in camp; while 91,380 of the fit single men between 18 and 45 had dependants.[12]

War service regulations provided that anyone who did not respond to the call up was liable to incur a penalty of six months imprisonment.[13] Given the heavy-handed approach and the men’s previous reluctance to enlist, it is not surprising that the call up met with significant resistance. On the face of it, the call up only required men to train in Australia and many men argued that this would cause hardship. In the context of the referendum they were opposing a real possibility of being sent to battle in Europe. As AG Butler has observed,

Examining officers were interested to find that, whereas in voluntary recruiting for the AIF they were constantly troubled by attempted impersonation in order to enter the force and by men who tried to ‘get past the doctor’ after multiple rejections, the precise opposite was now the case. Medical officers had to meet the determined, and very effective endeavours of a large number of ‘fit’ Australians to prove that they were ‘unfit’ for service.[14]

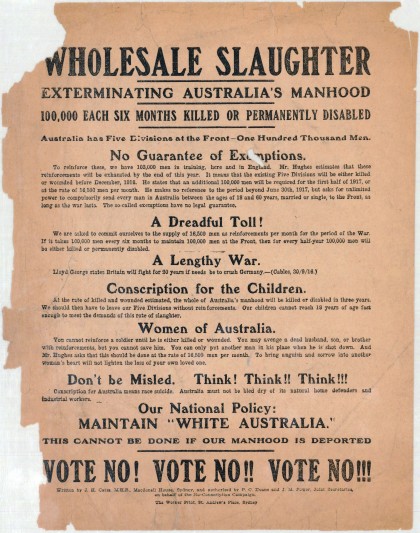

Contained in: Riley and Ephemera collection. Poster collection

1916, State Library of Victoria.

Exemption Courts

The Defence Act allowed exemption from military service on religious grounds.[15] War service regulations allowed further exemptions:

- Where it was in the national interest for a man to continue in his work, education or training;

- If military service would cause serious financial hardship;

- For the only son of a family;

- If at least half of the sons in a family enlisted;

- For sole support of aged parents, widowed mother or orphan siblings under 16 years of age or physically incapable of earning their own living.

These regulations were announced before the conscription plebiscite. A series of amendments were made until the regulations were repealed in December 1916.[16]

Local exemption courts were established to hear applications for exemption. Many were held during October before the plebiscite and some were held in November 1916. Approximately 190,000 men reported for medical examination in response to the call up. The number of defaulters is unknown. Of the men who reported as required, more than 45% applied for exemption. Nearly 40,000 men were unsuccessful.[17]

Sample records

Exemption court records are a valuable resource for family, local and social historians. Decisions of exemption courts were entered into registers. Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) now holds some of these exemption court registers from many locations throughout Victoria. It is useful to compare these registers with newspaper reports: combining information from the two sources often provides a different picture than would be suggested by either source alone.

Consider the case of three farming brothers from Strathbogie. The Euroa register records that Raymond Grot Barns was shearing and harvesting, and exemption was granted until 31 January 1917. Lawrence Henry Barns applied for exemption on the basis that ‘two brothers and myself manage farm for our widowed mother, farm about 650 acres, about 100 acres in crop, about 800 sheep and lambs to shear.’ He was granted exemption. The entry for Eric James Barns states: ‘Engaged cultivating land and keeping sheep. Assist to harvest 90 acres of crop. 700 ewes and lambs to shear. Also I am in ill-health.’ He was granted exemption until 31 January 1917.[18]

The local newspaper reported: ‘Lawrence Henry Barns, Raymond Barns and Eric Barns, three brothers, of Strathbogie, appeared, and, by arrangement, decided that the two last-named should go on January 31st. Lawrence Barns was then exempted.’[19]

There does not seem to be any consistent basis for recording details of exemption applications. Details of crops and stock are included in the Euroa register, as shown above. The same column in the Benalla register only records the regulation under which an application is made, for example, 35(1)(f), which covered the sole support provisions. There is even more variation in newspaper reports. Some papers baldly report the outcome of the hearings, listing names under headings of ‘absolute exemption’, ‘temporary exemption’ and ‘refused’. Other newspapers, such as the Euroa Advertiser, describe the hearings but do not provide a consistent level of detail. The Barns brothers’ crop and stock figures were not included but these details were included for some other applicants.

James Joseph Bamblett, an engine driver from Devenish, said he had a chaff-cutting plant and was the only one who could look after it. When his application was refused he said his brother could not look after the machine, and sending him meant his mother and sisters would starve. The register shows that he appealed against the decision but the appeal was struck out when he failed to appear before the district appeal court.[20] Herbert James Guppy, farmer, in his appearance,

said there was one other son. He was the only one to carry on. His brother did light work. One brother had been killed at the front. His brother could not manage horses, was dumb, and could not read or write.[21]

Guppy’s application was refused but he appealed against the decision. The appeal was allowed and exemption was granted.[22]

Courts for dealing with applications for exemption from military service were held before a police magistrate and a representative of the Defence Department. Sometimes this led to disagreements. Thomas Nicholas Costello of Kyneton applied for exemption on the basis of providing sole support for his widowed mother.

In response to Lieut. Lord, applicant said he gave his mother 25/ per week. Lieut. Lord: Well, if you went into camp you could afford to give her £2/2/ a week. Mr Bartold granted an exemption, but Lieut. Lord gave notice of appeal.[23]

The register shows that Costello was granted conditional exemption but has no details of an appeal. Lieutenant Lord’s opinions were also reported in other cases. George Walker Fowler, a Kyneton blacksmith, applied for exemption on the grounds of exceptional domestic financial obligations.[24]

Replying to Lieut. Lord, applicant said if he had to go into camp his father would have to close up the business. They had a lot of work on hand just now which was not finished. Lieut. Lord: So has the Empire, and unless you fellows come forward and do your duty it won’t be finished. The application was refused.[25]

PROV also holds some exemption certificates and applications for exemption for very limited locations (Rushworth and Fitzroy courts). The applications and decisions give an insight into the thoughts of some of the men and the impact the call up would have on their lives. Some examples of applications put before the Rushworth exemption court are given below.

Charles Corbett of Waranga Basin seemed to meet the exemption criteria, writing: ‘I am the [support] of a [invalid] Father and I also have two Brothers on Active service.’ His application was refused because he did not appear at the exemption court.[26]

Martin O’Leary of Waranga Basin was not sure of his birth date but thought he was over 35 years. His application was refused.[27]

Henry Bibby, a 29-year-old farmhand from Myola was eligible for exemption on the basis of being the only son. However he seemed to fear that this might not be sufficient and added to his application, ‘I crop in on the share and I have no body to look to my interest.’[28]

George Stephen Hilburn, a 21-year-old blacksmith from Rushworth, simply wrote, ‘I want to fix things up at home.’ His application was withdrawn.[29]

William Wason, a 26-year-old farm labourer from Myola, wrote: ‘I had taken a contract and have not got it completed. I am cutting wood and have not got it stacked and have not yet got paid for it also that I cannot pay my debts until I get paid myself, it will take me till harvest to get it finished.’ His application was refused. He was given seven days to report to camp.[30]

Similarly named, William Lee Wason, a 31-year-old farmer from Myola, wrote: ‘I cannot see my way clear to kill any man. I have got to assist in getting the harvest off. I am prepared to go with the Red Cross as a non-combatant.’ His scruples were disregarded. He was granted exemption ‘until 31 January 1917 to harvest’.[31]

John Aylward, a 33-year-old grocer from Waranga Basin reported indifferent health. ‘I have had a bad nervous breakdown and have never properly recovered. Insomnia and rheumatism varicocele.’ His application was refused.[32] The local newspaper reported that the Police Magistrate, Richard Knight, contended ‘that a month’s training in the open air would be a splendid tonic for nervousness and insomnia.’[33]

![Quick! [picture], Norman Lindsay 1879-1969](/sites/default/files/inline-images/McNeice-1-420x639.jpg)

Public perception

Mr Knight presided over several exemption courts in Victoria. He seems to have brought an element of showmanship to the hearings. It was noted that his humorous remarks and crisp comments often provided good copy for journalists.[34] Some proceedings were reported under headings such as ‘The comedy and drama of it’ and ‘Police Magistrate in great form’.

Despite whatever solemnity was attaching to the sitting of the court and its proceedings both applicants and those of the general public who were there out of curiosity, could not repress laughing – and often vociferously – at the form the applications took and the consequent remarks of Mr Knight, who throughout was in great condition and frequently very witty.[35]

Leslie John Sargood, a farmer from Gooram, applied for exemption on the grounds that he looked after his father’s farm and his only brother was in France. Mr Knight granted exemption but remarked that all fathers had suddenly become incompetent.[36]

Private financial information was also aired in the courts. William Denis Hoare, a farmer from Merton, cited his financial obligations. Having bought a farm two years earlier he was still in significant debt. He held 1293 acres and presented a financial statement in support of his application for exemption. Mr Knight told him ‘You are in a jolly good position.’ The case was adjourned pending receipt of a statutory declaration.[37]

Leslie Dighton of Euroa was employed as a groom at 15 shillings per week. He was the only single son at home and claimed that his mother depended on him. Mr Knight refused the application for exemption. He echoed Lieutenant Lord’s sentiments, noting: ‘The Government will give you 35s a week and your keep, and you would be more support to your mother if you went into camp.’[38]

Francis Vidler, a farm hand from Gooram, said he was in a bad state of health and not fit for camp life. He was suffering from appendicitis and, in response to the magistrate’s question, advised that he was about 12 miles from a doctor. Mr Knight responded, ‘If you go into camp and an operation is necessary you will be only 12 minutes from a doctor.’ The application was refused.[39]

Harry Wright, a 24-year-old farmer from Carag Carag, wrote in his application dated 14 October 1916 that he was the sole support of his parents and was married since 4 October. In the exemption court hearing he felt it necessary to add that he did not get married to dodge the war. Mr Knight replied, ‘Nobody said you did. If you did you had been dodging it a long time before that.’[40]

Lancelot Risstrom, a 23-year-old from Rushworth wrote, ‘I am the only remaining son also, that my father cannot possibly carry on with farming and contracting without my services. In the event of me being conscripted it would mean that my father would have to realize on his property, stock and plant.’ His application was refused. He was given seven days to go into camp, with Mr Knight’s comment, ‘It will only be a holiday for you.’[41]

Richard Knight was 53 years of age at the time of the exemption court hearings. His sons, Lieutenant (later Captain) Rupert Grenville Knight and Warrant Officer Cyril Frank Knight were at the war. Rupert Knight had been home for several months after suffering gas poisoning from the explosion of a Turkish mine. He re-embarked for service on 6 October 1916 as the exemption court hearings were beginning and later received the Military Cross.[42]

Perhaps it was the prospect of Mr Knight’s wit that prompted some men to withdraw their application in court. Perhaps some men felt that if they were to be sent to camp anyway, there would be greater honour in going voluntarily. However there was also a perception of unfairness in some cases:

One was struck by the obvious inability of the average young man to state his position clearly and concisely to a tribunal. While the authorities were perhaps right in decreeing that applicants for exemption be debarred from being represented by Counsel at the hearing of their claims … it still led in a few cases to results which were not satisfactory, either to the applicant, the presiding magistrate, or the public.[43]

![The Empire’s call [picture] [1914 – ca. 1918]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/McNeice-4-420x657.jpg)

Conclusion

Men who had not enlisted by the time the exemption courts were held had already resisted significant pressure to do so. The call up and associated exemption process was in full swing in the month leading up to the conscription plebiscite. This gave the public a taste of what conscription involved. Men could be ordered to abandon their obligations at short notice.

The records also convey a strong sense of suspicion that the reasons given by applicants for exemption were not regarded as genuine. Fingerprinting successful applicants for exemption certificates added an edge of criminality to proceedings. With or without a presiding magistrate’s wit, the public hearing of private matters represented the government’s forceful attempt to push men into service. Paradoxically this process probably contributed to the defeat of the conscription plebiscite.

After this result the exemption courts ceased and men were released from training camps. However the exemption court records of 1916 continue to provide a fascinating glimpse of the thoughts and lives of men who chose not to enlist. As Australia prepared to vote on conscription, the records also offer a snapshot of social attitudes at a pivotal moment in a young nation’s history.

Endnotes

[1] E Scott, Official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, Volume XI,Australia during the war, seventh edition, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1941, p. 874. The total number of men aged between 18 and 44 years is estimated at 1,077,000 from these figures.

[2] AG Butler, Official history of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918, Volume III, Special problems and services, first edition, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1943, p. 882n. Some men were rejected more than once.

[3] There is slight discrepancy between official reports and press reports of the enlistment standards in operation at different times: Scott, Official history of Australia, p. 439; Butler, Official history of the Australian Army Medical Services 1914–1918, Volume I, Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea, second edition, Australian War Memorial, Melbourne, 1938, pp. 20n, 525; Australian War Memorial encyclopedia, Enlistment standards, available at <http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/enlistment>, accessed 1 September 2015; ‘Volunteers wanted’, Argus, 21 December 1914, p. 10.

[4] ‘100,000 Men’, Argus, 5 June 1915, p. 17.

[5] Scott, Official history of Australia, p. 310n.

[6] ‘Call for more men’, Argus, 26 November 1915, p. 6.

[7] GH Knibbs, The private wealth of Australia and its growth together with a report of the war census of 1915, Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, Melbourne, 1918, p. 15.

[8] ‘Pressure to enlist’, Argus, 6 December 1915, p. 6.

[9] ‘Debate in the Senate’, Argus, 11 May 1916, p. 8.

[10] ‘Execution of Skeffington’, Argus, 12 May 1916, p. 7.

[11] EM Andrews, The Anzac illusion: Anglo-Australian relations during World War I, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1993, pp. 126–27.

[12] ‘Single men’, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1916, p. 6.

[13] War service regulations 1916: Statutory Rules, 29 September 1916, No 240, Commonwealth of Australia, reg. 9 (2).

[14] Butler, Official history, Volume III, Special problems and services, p. 888.

[15] Defence Act, No 20 of 1903, Commonwealth of Australia, sec. 61.

[16] War service regulations 1916: Statutory Rules, 29 September 1916, No 240, reg. 35 (1). Amended 18 October 1916, No 253; 20 October 1916, No 269; 10 November 1916, No 285; 22 November 1916, No 296. Repealed 6 December 1916, No 305.

[17] Butler, Official history, Volume III, Special problems and services, p. 889.

[18] PROV, VPRS 8509/P1 Local exemption court register of applications for exemption from military service, Unit 1: p. 9, entry 120, Barns, Raymond Grot; p. 9, entry 123, Barns, Lawrence Henry; and, p. 15, entry 294, Barns, Henry James.

[19] ‘District exemption courts’, Euroa Advertiser, 10 November 1916, p. 4.

[20] PROV, VPRS 1881/P0, Register of applications for exemption: 87th military sub-district, Unit 1, p. 1, entry 7, Bamblett. ‘Exemption court at Benalla’, Benalla Standard, 17 October 1916, p. 3.

[21] ‘Exemption court at Benalla’, Benalla Standard, 17 October 1916, p. 3.

[22] PROV, VPRS 1881/P0 Register of applications for exemption: 87th military sub-district, Unit 1, p. 2, entry 16, Guppy.

[23] ‘Kyneton exemption court’, Kyneton Guardian, 26 October 1916, p. 2.

[24] PROV, VPRS 2393/P0 Exemption court register of applications for exemption (from military service), Unit 1: p. 2, entry 13, Costello; and, p. 5, entry 35, Fowler.

[25] ‘Kyneton exemption court’, Kyneton Guardian, 26 October 1916, p. 2.

[26] PROV, VPRS 12455/P1 Applications for exemptions from military service, Unit 1, No. V/52/E/79, Corbett. The consignment includes a book of eleven certificates of exemption and two packages each containing approximately fifty applications for exemption. The applications include up to three numbering systems but are not arranged consistently by any order.

[27] Ibid., No. V/52/E/152, O’Leary.

[28] Ibid., No. V/52/E/75, Bibby.

[29] Ibid., No. V/52/E/170, Hilburn.

[30] Ibid., No. V/52/E/76, William Wason. ‘Rushworth exemption court’,Murchison Advertiser and Murchison, Toolamba, Mooroopna and Dargalong Express, 17 November 1916, p. 2.

[31] PROV, VPRS 12455/P1, Applications for exemptions from military service, Unit 1, No. V/52/E/128, William Lee Wason.

[32] Ibid., No. V/52/E/77, Aylward.

[33] ‘Rushworth exemption court’, Murchison Advertiser and Murchison, Toolamba, Mooroopna and Dargalong Express, 17 November 1916, p. 2. John Aylward is reported as John Hayward in the newspaper.

[34] ‘Police Magistrate Knight’, Shepparton Advertiser, 31 January 1918, p. 3.

[35] ‘Military exemption court’, Shepparton Advertiser, 23 October 1916, p. 3.

[36] PROV, VPRS 8509/P1 Local exemption court register of applications for exemption from military service, Unit 1, p. 3, entry 30, Sargood. ‘Exemption court at Euroa’, Euroa Gazette, 7 November 1916, p. 3.

[37] PROV, VPRS 8509/P1 Local exemption court register of applications for exemption from military service, Unit 1, p. 3, entry 36, Hoare.

[38] Ibid., p. 4, entry 54, Dighton.

[39] Ibid., p. 5, entry 67, Vidler.

[40] PROV, VPRS 12455/P1 Applications for exemption from military service, Unit 1, No. V/52/E/148, Wright. ‘Rushworth exemption court’, Murchison Advertiser and Murchison, Toolamba, Mooroopna and Dargalong Express, 17 November 1916, p. 2.

[41] Ibid., No. V/52/E/80, Risstrom.

[42] ‘Death of Mr Knight, P.M.’, Australasian, 5 June 1926, p. 50. ‘Police Magistrate Knight’, Shepparton Advertiser, 31 January 1918, p. 3. NAA: B2455, Knight Rupert Grenville. NAA: B2455, Knight Cyril Frank.

[43] Exemption court proceedings’, Euroa Advertiser, 10 November 1916, p. 2.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples