Last updated:

‘Beyond failure and success: the soldier settlement on Ercildoune Road’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 14, 2015. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © James Kirby.

This is a peer reviewed article.

This article will contribute to the wider academic debate on the uses of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ to describe soldier settlement in Victoria after World War I. The wider historiography emphasises the common factors that brought about a failure to live up to wider national ideals, economic objectives, and social expectations. However, most scholars neglect an investigation into the other aspects of the lives of soldier settlers which could be described as a success. Through the case study of the Ercildoune Road soldier settlement in Burrumbeet, Victoria, it will be shown how the farmers could be described as a success from both a personal and local perspective. The evidence for this contention is largely based on archival sources found at Public Record Office Victoria. Given the importance of context, a case will be made for caution in the use of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ as evaluative tools for constructing narratives on soldier settlement.

Soldier settlement in Victoria after World War I is often presented by the historiography as a story of lost hopes and unfulfilled expectations. Many were unable to live up to the idealistic images of the yeoman farmer and the ANZAC legend, to make a good profit, or to consistently provide as the breadwinner of the family. These points are well appreciated in the scholarship, demonstrating at least some sense of failure in the lives of soldier settlers. However, as will be shown in the case study of Ercildoune Road, such forms of assessment provide a narrow lens for examination, and do not formulate a comprehensive understanding of the lived experience of individuals or the community. In addition to reviewing the ‘tenor … of failure’ that pervades much of the literature, this article will observe the call of Michael Roche, whereby ‘the qualitative as well as quantitative dimensions of “failure” and “success” for soldier settlement need to be carefully reworked’.[1] The aim of this article is not to demonstrate how the government scheme was a success by rewriting a history of soldier settlement or presenting a ‘complete’ history of Ercildoune Road. Instead, the purpose here is, firstly, to show how some areas of soldier settlement could be defined as a success and, secondly, to contribute to the wider academic debate on the uses of ‘failure’ and ‘success’ as evaluative tools for constructing narratives of the past.

The concern with the historiography raised in this article is related more to the methods of analysis than an outright disagreement with the applied notion of failure. The few contrasting viewpoints depicting overall success across the state hold a similar shortcoming to those of failure in terms of their framework. The total experience of soldier settlement cannot be fully grasped by a simple label of either success or failure. The criteria for achievement can be clearly defined by scholars according to national, economic, and social expectations. Yet the enormous and complex process of soldier settlement featured multiple experiences and outcomes across diverse regions, personalities, and circumstances. The meso-level images of failure, for instance, must locate a means for conciliating with micro-level findings of success, whereby the differing observations bring clarity and understanding, and not necessarily contradiction. This article will utilise two key micro-level perspectives, showcasing the personalities of the settlement and the strength of the local community. Firstly, at the personal level, stories of individual triumph are found in those who persevered on the land for several decades in adverse conditions. Secondly, at the local level, one of the most important achievements for any soldier settlement is revealed to be the establishment of a strong sense of togetherness. Such an approach will reflect the nuanced reality of life in these communities and the ability of the soldier settlers to perhaps fulfil their own definitions of success.

The evidence for this article is based primarily on records gathered from Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), with significant supporting material from non-archival sources. The closer and soldier settlement files held at PROV are essential for tracing the basic development of individual blocks and the community as a whole. As noted by Charles Fahey, there is a need ‘to look at the complete range of soldier settlement files’.[2] In regard to just one settlement, substantial detail is found in correspondence between the farmers and government officials, statements of accounts, and expert appraisals of the land and the local area. A larger chronicle of soldier settlement in Victoria can easily omit a full study of a farmer’s settlement, advances, and revaluation files. The focus on a specific case study therefore allows room to consider a more comprehensive examination at the local level. Finer details can be found in separate files related to the individual blocks, the community, and individual projects, including the establishment of a local school. One main limitation of the PROV collection is the emphasis of the documents on matters strictly of concern to government officials, whereby the productive utility of the farmers is formally assessed rather than their entire lived experience. A broader picture is therefore found in combining these records with Jean McCartney’s local history of the settlement. As a descendent of Thomas McCartney, one of the original soldier settlers, Jean’s account contains an oral history with contributions from others who grew up on the farms as children. In regard to their family history on the land, the emotions and memories of the authors is a vital contrast to the more clinical overview contained in the files held by PROV. Nonetheless, the sobering assessment of the government records is required to obtain a balanced perspective, as oral histories can be subject to selective memory, nostalgia for an ideal past, and exaggerated childhood memories. Further information was gathered from historical newspapers made available online by the National Library of Australia, as well as the publications of local historical societies located at the State Library of Victoria. In tracing a local history of the settlement, both an objective and subjective portrait is provided by combining the sources at PROV and the record of Jean McCartney.

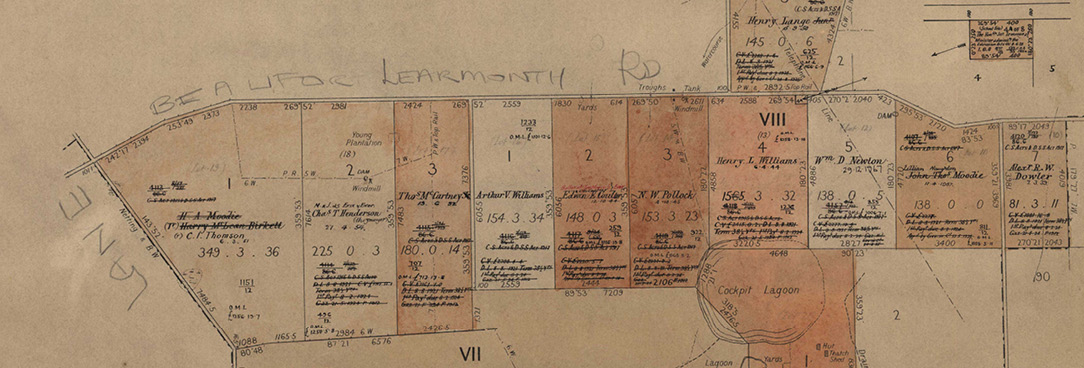

World War I was a major turning point in the history of the 20,000 acres (8093 hectares) Ercildoune Estate. Situated roughly 14 miles north-west of Ballarat, Thomas and Somerville Learmonth bought the land for £75,000 in the 1850s, later selling it on to Sir Samuel Wilson in 1873 for £236,000.[3] After the death of Wilson, the land was taken over by his sons Wilfred and Clarence on 19 June 1895. The estate was up for sale again at the end of World War I, following the death of Wilson’s sons in combat.[4] War veteran Major Alan Currie purchased 7,000 to 8,000 acres (2832 to 3237 hectares) in 1920. Another 3,735 acres (1511 hectares) were bought by the crown and opened to applications for closer and soldier settlement on 24 May 1921.[5] This study will focus on eleven of those blocks situated along Ercildoune Road, consisting of 1,793 acres (725 hectares) specifically for returned soldiers.

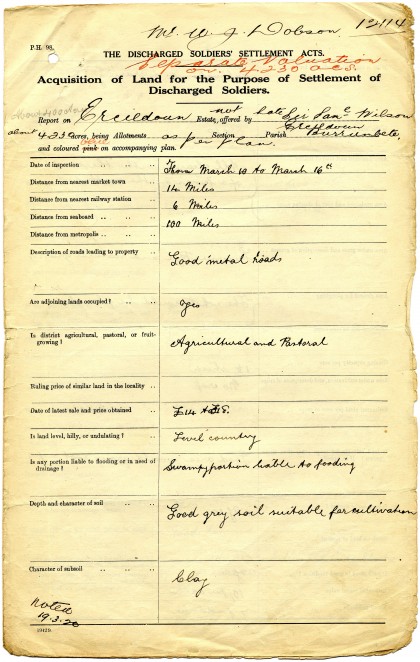

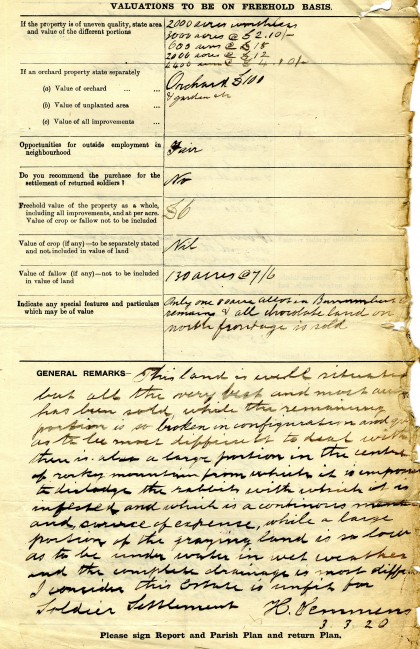

The quality of the blocks on Ercildoune Road varied extensively, yet there were strong advantages to the location. After surveying the land in February and March 1920, the inspectors claimed that ‘all the very best and most valuable land [on the estate] has been sold’.[6] While the area was portrayed in theArgus as ‘rich agricultural land and the remainder excellent grazing country’, the land evaluators strongly disapproved of the estate’s ‘numerous and extreme variation in description and quality’.[7] The earth ranged from ‘rich chocolate-volcanic soil’ and

‘good red soil’ for oats and crops; medium quality ‘light plain mixed farming and grazing land’; and a ‘large portion of poor lagoon land’ with ‘clay soil’.[8] With patches of ‘large swamps’ in the winter, the worst parts were dismissed as ‘practically useless’ and ‘so low as to be under water in wet weather’.[9] While one inspector concluded ‘the factors favouring suitability outnumber those against it’, and a second strongly favoured the land, a further two strongly declared it as ‘unfit for [s]oldier settlement’.[10] The lack of consensus brought considerable doubt over the suitability of the terrain, and the Closer Settlement Office did not accept applications for settlement for another fifteen months. However, in May 1920, a forceful appeal was sent to the office to declare that ‘the bulk of the estate’ should be reconsidered. Sent by a referee to the land evaluation, the letter implored them to take into account the recent heavy rainfalls, making much of ‘the country look the worst I have ever seen it’.[11] This plea was vital in persuading the board to re-examine the area again in September and October. While some continued to have serious concerns upon returning to the estate, all of the inspectors recommended the land for subdivision, further elaborating on the important advantages of the location. The settlement was close to the markets in Ballarat, the sheep and cattle yards were 12 miles (19.3 kms) away, and 2 chaff mills were within ‘easy distance’.[12] Survival on the land was not guaranteed for the returned soldiers who settled on Ercildoune Road, yet they were far from being situated on a hopeless prospect.

Narratives of failure: the historiography of soldier settlement

The literature contains three predominant narratives depicting failure in the history of soldier settlement, using the benchmarks of broader national ideals, economic objectives, and social expectations. The first measure emphasises the ‘sufferings of returned soldiers’ to show how they could not live up to the images of the yeoman farmer and the ANZAC legend.[13] Kent Fedorowich observed how the soldier settlers were expected ‘to become a symbol of post-war stability’ in a ‘cross fertilisation of the outback yeoman and ANZAC traditions’.[14] Within the rationale behind the scheme, Stephen Garton locates the ‘triumph of romantic fantasy over sober reality’.[15] Identified by Garton as a ‘flawed vision’, the concept of the self-sufficient yeoman farmer was believed to be the key to Australia’s rural development and future prosperity. This caused policy-makers, according to Marilyn Lake, to be misled into believing ‘that hard work and good intentions would guarantee success on the land’.[16] As a ‘wartime version of the bushman’, the ANZAC legend is also pinpointed by Fedorowich as leading to ‘romantic illusions … and misplaced assumptions of the potential of the returned man’.[17] Not only did these sentimental aspirations lead to failed policies, the soldier settlers were also destined to be seen as failures in their inability to live up to such unrealistic standards. However, according to McCartney, the soldier settlers on Ercildoune Road successfully lived up to both the yeoman and the ANZAC ideals. He argues the hardships ‘probably felt minimal to them’ due to their experience in war, except this time they were fighting for ‘their family’s sake and for their own piece of ground’.[18] However, pointing out either the failure or success of soldier settlers, on the basis of national dreams and myths, can only provide a limited framework for analysing their lived experience on the land. What can be overlooked is how the settlers saw themselves as individual farmers and collectively as a community, in accordance with their own beliefs and values.

The second historical narrative of failure stresses the inability of the farmers to pay off their debts and become profitable on the land. The soldier settlers were ‘bound to “fail”’, according to Joe Powell, as they were ‘increasingly required to give the country a worthwhile return on its investment’. In an era when ‘cost was rather dramatically underlined’, the Ercildoune Road soldier settlers would not be considered as a success under such terms.[19] By the start of World War II in 1939, all of the farmers on the settlement were in debt by at least £1,000 each, with a total cost of approximately £12,000. Monica Keneley provides an alternative economic approach in her study of the Western District between 1918 and 1930. She asserts the examples of ‘both alarming failures … [and] some very successful settlements’ demonstrate that ‘the policy was not a universal failure’.[20] ‘[T]he scheme on the whole appears comparatively successful’, according to Keneley, when ‘the level of forfeiture is taken as the measure of success and failure’.[21] Keneley, in strong contrast to Powell, may regard the entire Ercildoune Road settlement as a success simply because all farmers remained on the land until 1934. Yet, at that stage, the settlement could not be regarded in strict terms as either a success or failure. Some were forced off the land in coming years, while others would have to struggle for many decades before claiming their block under a freehold agreement. Furthermore, a resort to forfeiture was not necessarily a satisfactory marker of failure, particularly in a scenario where it was considered to be a sensible financial decision, avoiding further costs in the long-term.

The third historical narrative of failure underscores the inability of male soldier settlers to live up to their expectations as the breadwinners of the family. For Marilyn Lake, the goal to attain a ‘living wage’ was the standard all men had to achieve in order to ‘fulfil their family responsibilities’.[22] Given the ‘pitiful returns’ of soldier settlers, Lake contends that ‘these men were striving for the unattainable’ and were fated to regard themselves as failures.[23] On the basis of Lake’s interpretation of ‘personal failure’, the Ercildoune Road soldier settlers would not be regarded as a success.[24] During the 1920s, many families did not receive a consistent living wage, and often relied on their own stock to provide rations such as milk and cream.[25] Margaret, the daughter of John Moodie, acknowledged how ‘life was very labour intensive with few amenities’. She was aware of the hardships of the drought, the depression, and how the soldier settlers ‘strived long hours for just the basic necessities’.[26] This is confirmed by Shirley Boyle, the daughter of Jim Henderson, who recalls how ‘rabbits were in plague proportions’ and that ‘many families survived on them for food’.[27] However, the descendants still maintain a buoyant outlook toward their upbringing on the farm. Lionel Henderson, the son of Charles, reminisces about how they ‘were always very well looked after’.[28] This perspective is affirmed by Boyle who recollects how their parents did all they could to make sure they ‘never went to bed cold, hungry or dirty’.[29] Much like the other narratives of failure, an emphasis on broader social expectations reveals little on how soldier settlers could shape their own personal experiences.

Ill health, unfavourable markets, and poor land

The broader histories often describe the elements that led to failure, including ill health, unfavourable markets, and the poor quality of the land. However, many examples from Ercildoune Road show how these factors did not always result in a failure to survive on their block. Sergeant AE Loveride informed the Duke of Gloucester, during a visit to the district, that many settlers on Ercildoune Road had to survive despite being ‘handicapped often by physical disabilities’.[30] Those known to have suffered serious injuries during World War I include: Henry Lange who was wounded twice; James Henderson who was struck by shrapnel in his left thigh in France; and Edwin Eric Coulter, William David Newton, and John Thomas Moodie, who were all discharged as ‘medically unfit’.[31] As a result of the war, many farmers were physically disadvantaged on the land. Both the Williams brothers, Arthur and Henry, were noted in 1937 to have suffered ill health due to their war service; in 1941 Edwin Eric Coulter was said to have died ‘as a result of a war related illness’; and Lionel Henderson writes that his father, Charles, died in 1931 at the early age of 34 ‘as a result of the war’.[32] However, while war injuries had a debilitating effect on the settlers, this did not necessarily lead to an outright failure to live on the land. Many who physically suffered from the war survived for many decades before leaving the settlement, including Henry Williams who remained until 1944, Lange who held his block until 1950, and Newton who persevered until his death in 1967. Those who died as a result of their war experience were all survived on the land by their widows and descendants, such as Charles Henderson, Coulter, and Moodie. Therefore, the narratives of failure accurately specify the problems related to war injuries and illnesses. Yet they do not explain how the returned soldiers could survive on the land despite their physical disadvantages, and how this could be celebrated as an accomplishment on its own terms.

Within the historiography, the unfavourable markets are also often rendered as a prevalent source of affliction on the path to failure, yet this factor did not always correlate with financial ruin.[33] Like virtually all soldier settlers, the Ercildoune Road farmers struggled with low market prices for hay, wool, and sheep. As Lionel Henderson recalls, ‘times were very hard going’ when the ‘depression struck in 1929’.[34] Margaret Moodie also mentions how there was ‘little money for working long hours on the farm’ during the depression.[35] After surviving the economic downturn, many found extreme difficulty yet again during the late 1930s and early 1940s. In 1942, Norm Pollock insisted he was unable to make his instalment because the ‘chaff mill here has … stopped buying for some time’, thereby making it hard for him to make an adequate sale from his hay.[36] To make payments, quite often the settlers relied on the sale of their lambs during tough periods on the market. However, even the sale of sheep could suffer from a fall in prices. For at least a year, Moodie could not pay his instalments due to an ‘unfavourable season and low prices’ for sheep.[37] However, while all of the farmers on Ercildoune Road mostly relied on hay, wool, and sheep for their returns, not all were forced off the land. Many of the settlers could find other means to survive and make money during bad periods. Moodie worked as a carpenter, James Henderson became a Clydesdale breeder, Arthur Williams raised thoroughbred horses, and Tom Coulter’s wife, Mary, was a teacher at Brewster and Burrumbeet.[38] The unfavourable markets led to difficulty on the land, yet the broader narratives cannot account for how soldier settlers could confront and even overcome their various challenges.

The wider scholarship depicts the poor quality of land as another leading cause of failure yet, once again, this adversity did not bring about a universal incapacity to make a living on the farm. Many of the farms on Ercildoune Road suffered from small block size, flooding, and drought.[39] During the initial inquiries into the area, the District Inspector strictly recommended the land only if the blocks would be subdivided into ‘300 acre lots’.[40] Yet the eventual average size of the allotments was much lower at 163 acres (65 hectares), almost half the recommended size. The District Inspector also raised concerns over the quality of the land whereby, out of Thomas McCartney’s 180 acres (72 hectares), 60 acres (24 hectares) were designated as ‘low lying swamp of little value’. With just 153 acres (62 hectares), Norm Pollock’s block suffered from a ‘[d]epression running through the block which carries a lot of water in winter, mak[ing] the block rather a wet property’.[41] On William Newton’s farm, it was deemed ‘there would not be more than 5 or 6 acres of first class Ercildoune Rd country’ with the potential for growing crops, and ‘buildings and yards are erected’ on that portion.[42] However, out of all those known to have held a poor block of land, Newton, McCartney, Moodie, and Charles and Mary Henderson still found a way to survive for several decades. To make payments and maximise their crop yields, many settlers began sharefarming on each other’s blocks, as well as outside of Ercildoune.[43] The narratives of failure highlight the genuine challenges that often forced soldier settlers off the land, yet they are unable to explain how many could survive on the land despite their predicaments. Their ability to persist marks an important limitation for the use of the term failure to chronicle the lives of soldier settlers. The incidence of perseverance may be inadequate as an indicator of overall success, yet such examples of vigorous personal endeavour complicate any attempt to craft a sweeping image of failure.

Two personal histories: the stories of Mary Henderson and John Moodie

Mary Henderson’s story is an example of how those on the farm could survive despite ill health, unfavourable markets, and poor land quality; all factors cited within the scholarship as common causes of failure. After his return from wartime service in France, Charles Henderson, Mary’s husband, seemed to occupy a relatively favourable position to become a success as a soldier settler. He had prior experience working on his father’s 550 acre (222 hectare) farm in Weatherboard, and satisfactorily paid his instalments through to the late 1920s. Furthermore, he had been distinguished for his bravery and accomplishments in the war. Charles, appearing to meet the ideal of the ANZAC legend, was awarded the Star, the British War Medal, and Victory Medal.[44] However, upon his early death in 1931 as a result of war injuries, despite all of his prior efforts, there was a great risk his family would fail and be required to leave the land. Yet the experience and outcome of any soldier settlement block expanded beyond merely the actions of returned servicemen themselves, particularly in regard to their spouses and descendants. In the event of such an untimely passing, the remaining tasks could be passed on to any family members that persisted on the farm, whose capacity, circumstances, and efforts would thereby determine the overall failure or success of the soldier settlement block.

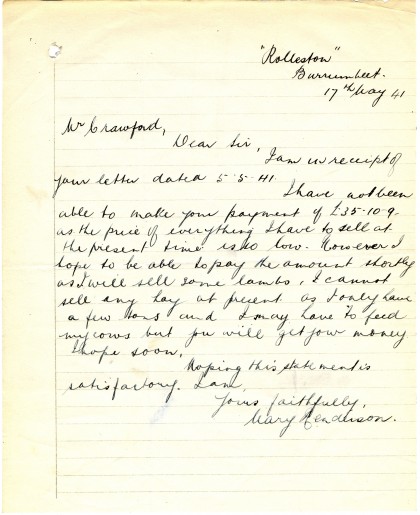

Not only did Mary Henderson have to fulfil the economic obligations of the farm, as required by any male soldier settler, but also to counter the negative social expectations of women performing such work. As her son Lionel explained, ‘it was not seen to be possible in those days that a woman’ could manage a farm on her own. Left with only the occasional help of her three children and a hired hand, Lionel recognises the ‘times were hard’ and she was ‘nearly forced off’ the block.[45] For almost every six monthly instalment during the 1940s, she had to pen letters to the District Inspector, promising that while ‘[i]t seems I am scheming … such is not the case’ and that ‘you will get your money I hope soon’.[46] She started off the decade in bad health having ‘been ill in hospital’.[47] When she returned to the land, she soon found difficulty in selling her farm produce. This was shown on 17 May 1941 when she wrote that she could not make her instalment of £35 due to ‘the price of everything I have to sell at the present time [being] so low’.[48] Both flooding and drought were also a significant problem, as seen on 6 October 1941 when she ‘only had 3 tons of hay to sell’ due to flooding, and on 11 June 1943 when she wrote that ‘I am losing my sheep’ as a result of a very wet season.[49] By November 1945, her sheep numbers had dropped from over 500 to just 90 ‘owing to the drought’. In what was thought to be a good turn of fortune, by 10 November 1945 she had managed to cultivate 60 acres (24 hectares) of good harvest for selling hay.[50] However, she had to delay making her payment again on 19 February 1946 because, as she laments, ‘there is not any market at the present time for hay’.[51] Despite the multiple challenges, Mary Henderson persisted long enough to be able to obtain the land under a freehold agreement in March 1954. As of September 1997, the land of Charles and Mary Henderson remained under the ownership of their son Lionel and his wife Joyce.[52] Mary did not fully live up to the high hopes for soldier settlement. However, she had proven her ability to survive on the land, to meet the economic requirements normally demanded of returned soldiers, and to overcome the gendered perceptions of the time period. In bringing to completion the work begun by her husband as a soldier settler, Mary’s experience may be seen as a personal success story when evaluated on its own merits.

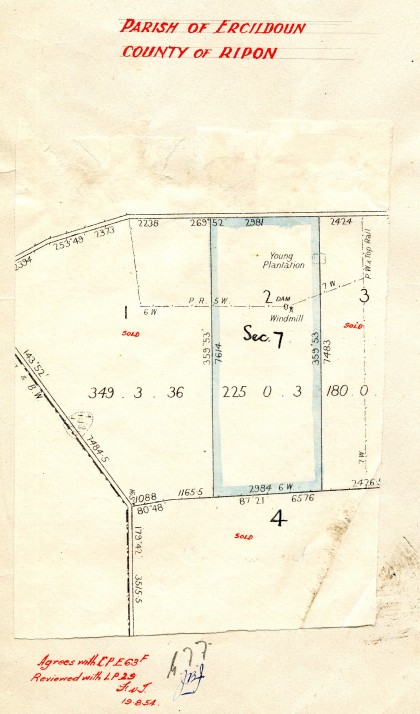

A sketch of the Henderson block, PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun.

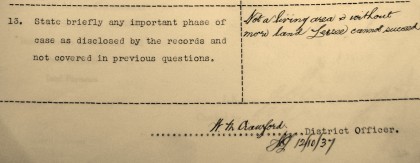

The ability of soldier settlers to prevail over the obstacles of ill health, unfavourable markets, and poor land quality is also manifested in the story of John Moodie. In a 1937 report to the Closer and Soldier Settlement Commission in Ballarat, the District Inspector found, in regard to Moodie’s block, that ‘without more land [the] Lessee cannot succeed’.[53] When writing to have his liability reduced further, Moodie expressed further doubts about his state of affairs. He specified his problems with a ‘light harvest’, the need to ‘provide for 5 dependents’, and his small level of income.[54] Much like Mary Henderson’s situation, Moodie struggled to make his instalments on time, causing him to be in regular correspondence with the Department of Crown Lands. On 17 May 1940, the Pro-Secretary wrote to Moodie demanding to know why he had not paid his regular instalment of £31 on time, adding that his ‘failure to reply’ would be ‘viewed seriously’.[55] In a letter sent just over a week later, Moodie explained his delay was due to a substantial ‘loss in flooding’ and the poor market price for hay.[56] The government’s response was unforgiving, notifying Moodie that ‘no further extension of time will be granted’ unless he paid by the end of June.[57] Unable to make the payment by such time, Moodie was told on 11 July that if he could not transfer the required amount within ten days, the Pro-Secretary would ‘recommend that the question of cancelling your lease be considered’.[58] It was not until the District Inspector interviewed Moodie and reported he was ‘not in a position to pay at the present time’, due to being ‘flooded and also loss of sheep’, that the Department of Crown Lands officials accepted Moodie’s request for extra time.[59] Similar to Mary Henderson’s story, John’s wife, Lillian, continued on the farm after his death on 1 November 1953. Despite the land being ‘neglected owing to 5 years [of] illness of the late Mr J. Moodie’, she successfully maintained the farm with the help of her son John.[60] Lillian Moodie was also able to attain a freehold agreement in 1957, and eventually passed on the land to her son and his wife Elaine. Like the Hendersons, the family is confirmed to have stayed there until at least September 1997.[61] The Moodie story reveals the contextual nature of failure and success, whereby the family would not have met the wider expectations of soldier settlement, yet they far exceeded the forecast of the District Inspector.

A local history: the founding of a community on Ercildoune Road

The settlement on Ercildoune Road may not have developed into a prosperous enterprise, yet it evolved into a cohesive social community. Gwen Rendell, daughter of Jim Henderson, reflects on their sense of togetherness in a verse from her poem ‘The Soldier Settlers of Ercildoune’. As she writes, ‘The comradeship they made over there / They brought home with them again / … But friends they made along that road / It stayed with them for good / A helping hand to one another / Whenever each one could’.[62] The sentiment of Rendell’s verse is consonant with McCartney’s recollection that ‘there did appear to be an aura of friendliness’ and ‘a unity of defence of one another’. In the earlier years, often the ‘[n]eighbours would help’ when threshing the ‘grain from the oaten hay’.[63] Lionel Henderson also recalls how the soldier settlers ‘were all pretty good mates and seemed to help one another’.[64] Away from the farms, the Ercildoune Road settlers regularly attended dances and events together at the Burrumbeet Hall.[65] Even closer to home, Rendell remembered ‘there was plenty of entertainment’ and dancing at the school hall.[66] The farmers would often play cards on Saturday nights and would gather ‘for a sing song around the piano’, particularly on ‘birthdays or other celebrations’.[67] With such a strong sense of togetherness, whenever a family left the settlement it was seen as a significant loss to the community. Alexander Dowler’s son, Len, recalled the time when their family was given a clock as a going away present. He states that he still has it in his possession and ‘it still goes’.[68] The establishment of such social cohesion and harmony is a success story that is rarely accounted for in the broader narratives of failure. The government may have founded the settlement, but it was the settlers who founded the community.

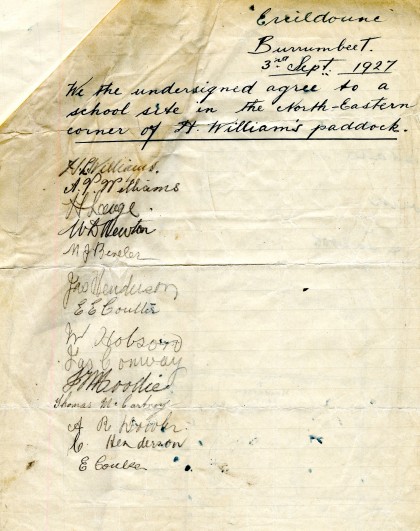

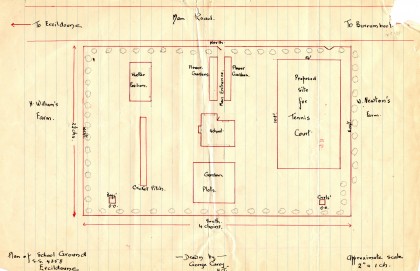

PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 3037, Ercildoune school no. 4358, Harry Gill, letter to the Director of the Education Department, 10 September 1927. Gill attached a list of signatures by local farmers, dated 3 September 1927, who approved the location of the school site.

The construction of the Ercildoune Road Primary School was a definitive movement in the establishment of the community. Alexander Peacock, the Minister for Education at the time, was approached by a spokeswoman for the Ercildoune Road soldier settlers in April 1924.[69] She pointed out that ‘[t]he Settlement is rapidly growing and further settlement will take place if a school is provided’. By the mid-1920s, almost all of the settlers were starting a family. Nine children were ready to attend school in 1924, with fifteen expected to be ready by 1927.[70] After having their request denied, the parents confronted the minister again three years later while he was attending a function at Ercildoune House on 20 January 1927. Following a strong recommendation from the District Inspector, remarking that he had ‘every confidence that the school will gradually increase in numbers’, the school was approved in February.[71] However, they were delivered a heavy setback when Major Currie demanded £100 from the Victorian Government to allow a school to be established on an acre of his property. The Government Valuer protested that this was ‘much in excess of surrounding values’ and made it clear that they could not pay such a large amount for a school.[72] To rescue the community’s hopes, Henry Williams offered up an acre of his land for a meagre £30. This was a considerable sacrifice because, as argued by the District Inspector, the ‘area is rather small’ and ‘these soldier settlers state that they require all the land they have’.[73] McCartney underlines the school’s opening on 11 August 1928 as ‘one of the best days of the parents’ lives’. This included an opening ceremony with over 200 people in attendance. Lady Peacock, in her speech at the school, ‘eulogised the parents for the deep interest they were taking’ in the welfare of their children. The settlers also worked together to build a shelter shed in 1929, largely drawing on their own money and the ‘voluntary labour of the parents and school committee’.[74] At around this time, many of the settlers were paying off high levels of debt, putting in long hours on their farms, and struggling through the depression. While they encountered difficulty on their individual blocks, they remained committed to the long-term needs of the community. Small success stories such as these are often disregarded by scholars who attempt to build a more extensive narrative, yet within a local context they play a crucial role in the overall lived experience of those on the land.

The fond memories of the children on Ercildoune Road further expose the need for more intricate accounts of the lives of soldier settlers. In another verse of Gwen Rendell’s poem, she suggests all the descendants should ‘think of the wonderful times we had / When each one of them was here’.[75] In reaffirming this sentiment, McCartney declares the descendants should not look back on the earlier days with horror or a sense of failure. Alternatively, they should think of their parents’ ‘courage, hard work, kindness and enjoyment’.[76] The descendants recognise the struggles and the hardships, yet they also proudly discuss their more enjoyable experiences. Lionel Henderson remembers the end of year school concerts, and both Lionel and Shirley Boyle recall the fun of chasing and shooting rabbits.[77] A further tribute is paid by Margaret Moodie to her early years of education and the school’s sporting activities. Amidst the drought of the 1940s, Val Lange humorously recounts the time when their ‘cows ate the curtains’ after the window of the house dairy was left open.[78] After Alexander Dowler left the land in 1939, his son Len referred to it as ‘the saddest time of my life’.[79] Beyond the positive memories, Gwen Rendell appreciates how their parents left them with a strong sense of community. As she writes, ‘Now along that road of Ercildoune / Where we all grew up so proud / Our friendships never faltered / Because of our soldier Dads’.[80] McCartney concludes, accordantly, that with ‘dedication to the life their parents taught them in’, a number of blocks are still owned by the descendants of the soldier settlers.[81] A feeling of community spirit may be characterised as merely a necessary component of survival. However, the ability to find collective ways to enjoy life on the land, build shared memories, and develop inter-generational bonds between families, are a meaningful set of accomplishments that would not be possible without such social unity. The strong legacy of togetherness on Ercildoune Road indicates that there is much more to the history of soldier settlement than a story of failure.

Conclusion

These examples of relentless personal endeavour, and the evidence of a longstanding sense of community, demonstrate some important limitations when identifying failure in the lives of soldier settlers. The matter of context is crucial for determining success or failure, as well as the boundaries for such labels. The broader narratives provide insights into the misleading ideals of the yeoman farmer and the ANZAC legend, the shortcomings of soldier settlers in making a profit, and their inability to meet their social expectations as the ‘breadwinner’ of the family. Yet given their broad viewpoints, these descriptions can neglect an investigation into the other aspects of their lives which can be described as a success. The wider narratives can be profound in illustrating the problems faced by soldier settlers; including their ill health, unfavourable markets, and the poor quality of the land. However, they lack a full explanation as to how the farmers could survive despite their unfavourable conditions. By investigating two personal histories, it was uncovered that Mary Henderson and John Moodie found success individually in their ability to persevere on the land. They did so for many decades in a dispiriting position and eventually passed on the land to their children. Through a localised history, it was revealed the settlers found success collectively in their ability to enjoy life together on the land and to establish an enduring sense of community. A great degree of caution is therefore warranted in the use of both ‘failure’ and ‘success’ in crafting narratives of the past on soldier settlements and soldier settlers. Histories of this topic in future demand a more fine-grained approach, unearthing the complex reality of life on the land, and outcropping the simplistic narratives. The soldier settlers were worth far more than the sum of their so-called failures and successes.

Endnotes

[1] Michael Roche, ‘World War One British Empire Discharged Soldier Settlement in Comparative Focus’, History Compass, Vol. 9, No. 1, January 2011, pp. 6 and 10.

[2] Charles Fahey, ‘Review: The Limits of Hope by Marilyn Lake’, Historical Studies, Vol. 23, No. 90, April 1988, p. 141.

[3] Ercildoune Homestead, ‘Ercildoune history’, available at <http://www.ercildoune.com.au/index.php?page=history>, accessed 5 June 2012; PL Brown, ‘Learmonth, Somerville (1819–1878)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/learmonth-somerville-2836/text3059>, accessed 6 June 2012.

[4] ‘Death of Sir Samuel Wilson: a long illness’, South Australian Register, 13 June 1895, p. 5, available at <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/54461759>, accessed 5 June 2012.

[5] ‘Ercildoune sold’, Argus, 7 October 1920, p. 6, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4579357>, accessed 5 June 2012.

[6] PROV, VA 538 Department of Crown Lands and Survey, VPRS 5714/P0 Land Selection Files, Section 12 Closer Settlement Act 1938 [including obsolete and top numbered Closer Settlement and WW1 Discharged Soldier Settlement files], Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, K Pennmen, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 3 March 1920.

[7] ‘Ercildoune estate’, Argus, 16 May 1921, p. 6, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.newsarticle1757111>, accessed 12 June 2012; PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, John H Gardiner, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 10 March 1920.

[8] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, John H Gardiner, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 10 March 1920, and Read, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 6 March 1920.

[9] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, K Pennmen, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 3 March 1920.

[10] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, Charles Walker, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, March 1920, and John H Gardiner, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, 10 March 1920.

[11] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, H Abbott, letter to the Secretary of the Closer Settlement Office, 14 May 1920.

[12] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, unnamed evaluator, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, November 1920, and Walker, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, October 1920.

[13] Monica Keneley, Land of Hope: Soldier Settlement in Western District of Victoria, 1918–1930, Deakin University, Geelong, 1999, pp. 1–2.

[14] Kent Fedorowich, Unfit for Heroes: Reconstruction and Soldier Settlement in the Empire Between the Wars, Manchester University Press, Manchester and New York, 1995, p. 146.

[15] Stephen Garton, The Cost of War: Australians Return, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p. 133.

[16] Marilyn Lake, The Limits of Hope: Soldier Settlement in Victoria 1915–38, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, p. 64.

[17] Fedorowich, Unfit for Heroes, pp. 146–7 and 177.

[18] Jean M McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers of Ercildoune Road (1914–1918), Jean M McCartney, Burrumbeet, Victoria, 2007, p. 4.

[19] JM Powell, ‘The Debt of Honour: Soldier Settlement in the Dominions, 1915–1940’, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 8, 1981, p. 71.

[20] Keneley, Land of Hope, pp. 1 and 11–12.

[21] Monica Keneley, ‘Land of Hope: Soldier Settlement in the Western District of Victoria 1918–1930’, Electronic Journal of Australian and New Zealand History, April 2000, available at <http://www.jcu.edu.au/aff/history/articles/keneley2.htm>, accessed 6 June 2012.

[22] Lake, Limits of Hope, pp. 173–4.

[23] Ibid., p. 174.

[24] Ibid., p. 100.

[25] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 5.

[26] Margaret Moodie, ‘John Thomas and Lillian Moodie – Block Number 11’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 21.

[27] Shirley Boyle, ‘Jim Henderson – Block Number 8’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 17.

[28] Lionel Henderson, ‘Henderson – Block No. 18’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 14.

[29] Boyle, ‘Jim Henderson’, p. 18.

[30] ‘Royalty in the Mallee – duke drives car’, West Australian, 1 November 1934, p. 19, available at <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32801046>, accessed 30 April 2012.

[31] Learmonth and District Historical Society, Duty Nobly Done, Learmonth and District Historical Society, Learmonth, Victoria, 1995; PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 700, Norman H Malcolm, ‘Farm Allotment’, 7 June 1921.

[32] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 708, WM Crawford, ‘Statement for Re-Assessed Liability’, 18 October 1937, and WM Crawford, ‘Statement for Re-Assessed Liability’, 29 November 1937; Henderson, ‘Henderson’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 14; Clare Madden, ‘Mr E. C. (Tom) Coulter – Block Number 5’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 20.

[33] The Rural Reconstruction Commission, Settlement and Employment of Returned Men on the Land, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, 18 January 1933, p. 4.

[34] Henderson, ‘Henderson’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 14.

[35] Moodie, ‘John Thomas’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 21.

[36] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 129, Norm W Pollock, letter to the Department of Lands and Survey, 6 June 1940.

[37] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, James Moodie, letter to the Secretary for Lands, 14 January 1940.

[38] Gwen Rendell, ‘James Henderson – Block Number 8’, in McCartney (ed.),The Soldier Settlers, p. 19; Jean McCartney, ‘Mr A. V. Williams – Block Number 16’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 22; Madden, ‘Mr E. C. (Tom) Coulter’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 20; Moodie, ‘John Thomas’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, pp. 20–1.

[39] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 4.

[40] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 1155, Estate 13819, H Allan Currie, Ercildoun Burrumbeet, Walker, ‘Acquisition of Land for the Purpose of Settlement of Discharged Soldiers’, October 1920.

[41] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 170, J Campbell, ‘Valuation – Land and Improvements’, 25 September 1937.

[42] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 129, Campbell, letter to the Chief Inspector, 27 October 1927.

[43] Henderson, ‘Henderson’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 14.

[44] Learmonth and District Historical Society, Duty Nobly Done.

[45] Henderson, ‘Henderson’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 14.

[46] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 17 May 1941, and Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 6 October 1941.

[47] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 28 October 1940.

[48] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 17 May 1941.

[49] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 6 October 1941, and Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 11 June 1943.

[50] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 10 November 1943.

[51] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 201, Item 496/12, Charles Thomas Henderson the Younger, Deceased Estate Ercildoun, Mary Henderson, letter to Crawford, 19 February 1946.

[52] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 13.

[53] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, Crawford, ‘Re-Assessment of Liability’, 12 October 1937.

[54] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, John Thomas Moodie, letter to Appeal Committee, 15 October 1938.

[55] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, Butler, letter to John Moodie, 17 May 1940.

[56] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, John Moodie, letter to Butler, 25 May 1940.

[57] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, Butler, letter to John Moodie, 29 May 1940.

[58] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, Butler, letter to John Moodie, 11 July 1940.

[59] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, Crawford, ‘Returned Copy for Inspector, Ballarat’, 18 July 1940.

[60] PROV, VPRS 5714/P0, Unit 682, W Leask, letter to Officer in Charge, Geelong Branch, 9 November 1954.

[61] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 13.

[62] Gwen Rendell, ‘The Soldier Settlers of Ercildoune’, in McCartney (ed.),The Soldier Settlers, p. 2.

[63] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 3.

[64] Henderson, ‘Henderson’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, pp. 14–15.

[65] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, pp. 3 and 6.

[66] Rendell, ‘James Henderson’, p. 19.

[67] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 9.

[68] Len Dowler, ‘Alexander R Dowler – Block Number 10’, in McCartney (ed.),The Soldier Settlers, p. 14.

[69] Ken James, Muddy Water: A History of Burrumbeet, Learmonth and District Historical Society, Camberwell, Victoria, 2007, p. 144.

[70] PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 795/P0 Building Files: Primary Schools, Unit 3037, report on Alexander Peacock’s visit to Addington School, 7 February 1924.

[71] PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 3037, Harry Gill, letter to the Director of the Education Department, 12 February 1927.

[72] PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 3037, government valuer, memorandum to the Pro-Secretary for Public Works, 11 August 1927.

[73] PROV, VPRS 795/P0, Unit 3037, Harry Gill, letter to the Director of the Education Department, 10 September 1927.

[74] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 8.

[75] Rendell, ‘The Soldier Settlers’, p. 2.

[76] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 13.

[77] McCartney, ‘Thomas McCartney – Block Number 17’, in McCartney (ed.),The Soldier Settlers, p. 22; Boyle, ‘Jim Henderson’, p. 17; Henderson, ‘Henderson’, p. 14.

[78] Val Lange, ‘Henry Lange – Block Number 9’, in McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 16.

[79] Dowler, ‘Alexander R. Dowler’, p. 14.

[80] Rendell, ‘The Soldier Settlers’, p. 2.

[81] McCartney (ed.), The Soldier Settlers, p. 13.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples