Last updated:

‘The Royal Oak Hotel, corner of South and Raglan streets, Ballarat’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 8, 2009. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Helen Dehn.

The Royal Oak Hotel in Ballarat is today a clean and convivial spot to spend time with friends and colleagues. It was not always this way, however. In the nineteenth century it was not uncommon to see men and women ‘in a helpless state of drunkeness’ outside hotels, and these establishments wereavoided by ‘respectable’ people.

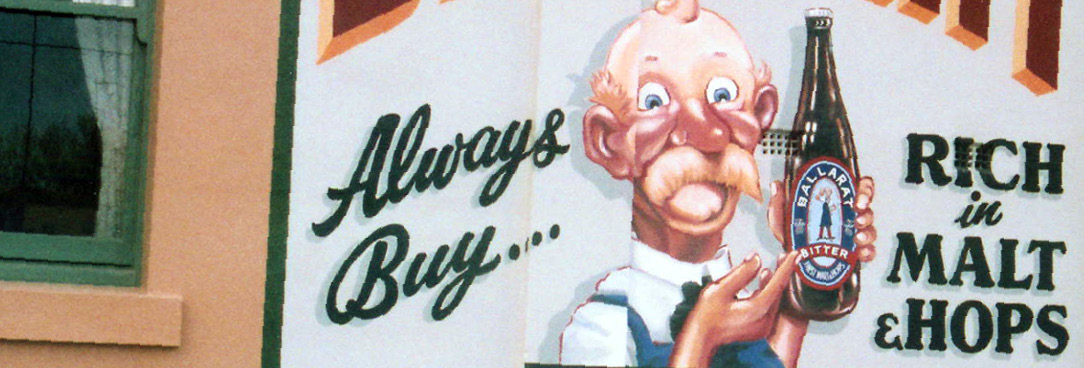

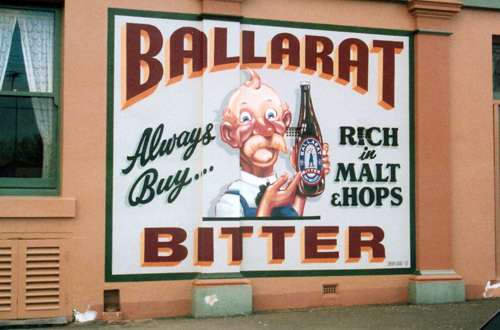

Some of the changes to the hotel culture were driven by the temperance movement. Though many of Ballarat’s hotels resisted the push for change, public drunkenness had become a significant problem and various groups campaigned in the interests of wives and children. The hotel trade received a boost in 1926 with the launching of the Ballarat Bertie beer label, featuring Bertie the cellarman. The advertising campaign to popularise Bertie was inspired, and the advertisements were large and varied. The reformers fought back by insisting that meals must be served with drinks, and so the winner in this battle turned out to be the patron.

Since 1994 the Royal Oak’s patronage has increased, with the dining record standing at 102 meals served in one night. The hotel has become very much a home away from home for many, and is now a valued social asset.

Introduction

Ballarat’s early years were tumultuous. The town had been flooded with gold seekers during the 1850s and alcohol was both a social lubricant and an escape for those who found themselves in straitened circumstances far from home. In an effort to minimise the ill effects of alcohol, Governor La Trobe had imposed prohibition on the goldfields, but this action gave rise to numerous ‘sly grog’ outlets, which competed for trade with licensed premises. Police raids were frequent and large quantities of ‘grog’ were often seized.[1] According to historian WB Withers, cited in the centenary edition of the Courier, there were 477 licensed hotels in Ballarat in 1867 and all hotels remained open until 1.30 am.[2] Hotels were not then viewed as fit places to entertain respectable men, much less their families, and it took many years and the efforts of various groups before the situation was improved. One of Ballarat’s more substantial hotels was the Royal Oak and its first publican was John Ellis.

According to the rate book of 1858, John Ellis owned a store at 10 Raglan Street Ballarat that was rated at £6 5s per annum.[3] He was also shown as the owner of a brick house on the west side of Raglan Street with a net value of £126.[4] This house became the Royal Oak Hotel, although it was originally named the Sign of the Castle and Ball.

An application was filed by John Ellis of Raglan Street with the licensing registrar for a hearing on 2 October 1866 ‘for house situate at Raglan Street aforesaid, his own property, consisting of a brick building containing a bar, bar parlour, sitting room, six bedrooms, kitchen etc. and to be known as the Sign of the Castle and Ball Hotel’.[5] Ellis’s application was successful as his name was listed in the hotels index of 1866, although the index recorded the name wrongly as the Castle and Bowl Hotel. Ellis moved into the hotel, and the store at 10 Raglan Street, which appeared to have been his prior dwelling, was offered for private sale shortly afterwards with negotiations conducted at the hotel.[6]

The 1867 rate book lists John Ellis as the owner of a brick hotel on the north side of South Street, but does not mention the hotel by name. It is evident, though, that entry to it was no longer from Raglan Street but from South Street. This was confirmed by the 1868 rate book, which listed Ellis as the keeper of a brick hotel consisting of a bar and eight rooms in South Street on the north-west corner of Raglan Street.[7] Further along South Street was vacant land owned by the Kohinoor Gold Mining Company, while on the corner of South and Errard Streets was a site measuring approximately 101 x 117 links[8] (approximately 66 x 77 ft or 20 x 23 metres), which was purchased by J Roberts and others, trustees of the United Methodist Free Church, in May 1889. A brick church was opened on this site in May 1890. These three properties, the hotel on one corner, the church on the other, and the mine in the middle, form the dynamic of interest to this historical sketch, and although the establishment of the hotel preceded that of the church by some decades, the two establishments represented a continuing and sometimes bitter division between different perceptions of respectability, New World (male) identity and manhood.

Sitting on gold

The Sign of the Castle and Ball Hotel had become the Royal Oak Hotel by the time the licence changed hands on 20 June 1873, going from John Ellis to Thomas Sanderson, who retained the licence until 21 October 1875. Gold was Ballarat’s primary attraction though, and a veritable army of male gold seekers gave rise to Ballarat’s many hotels. In 1867, there were 230 registered mining companies in Ballarat and on the north side of South Street, beside the Royal Oak, was the main shaft of the Great Eastern Company, which was registered as working the Malakoff Lead. Mining companies in the vicinity included the Sons of Freedom, the Great Western, the British Company, and Hawthorn’s. The Great Eastern Company of ninety-six shareholders was said to have held twelve claims on the Malakoff Lead, but only one of these appeared on Baragwanath’s geological and topographical map of 1917: the one adjacent to the Royal Oak Hotel.[9] During the 1850s there was a lot of confusion as to which lead was being worked by which company, and lawsuits to resolve disputes were common.

A succession of licensees

After 1875 there was a succession of licensees trading from the Royal Oak. After Ellis and Sanderson came John Thomas, the licensee from 22 October 1875 until 20 June 1878, and after Thomas a woman named Winifred O’Meara traded from 21 June 1878 until 1889. Both Thomas and O’Meara were subject to unfortunate incidents during their tenures. In the case of Thomas, it was an incident that resulted in a man’s death. The man was an engineer named Edward O’Brien, aged 39, and employed at the works of Davey Brothers.

O’Brien was lodging at the Royal Oak Hotel in one of the bedrooms upstairs when he met with an accident on Tuesday 23 January 1877 at about 1.00 in the morning. According to a report in the Evening Post, O’Brien had retired to his room

but feeling the atmosphere rather close, he proceeded to open the window from the top. A Venetian blind was fixed on the inside of the window, which precluded O’Brien from prising the sash open. For this purpose O’Brien got outside and while endeavouring to pull the sash down his hands slipped from the woodwork and he fell onto the pathway below…sustaining some very nasty cuts about the head and face together with some bruises and he suffers rather much from the shaking. He was picked up insensible some time after the accident and removed to hospital where he now remains, doing as well as could possibly be expected.[10]

According to a Ballarat inquest held in 1877, O’Brien subsequently died of injuries sustained from falling out of a window.[11]

John Thomas evidently offered lodgings to his patrons, and while it cannot be assumed that the patron was inebriated, his decision to open the upstairs window while perched on the narrow ledge outside (even if seated) is not one that many sober men would make.

Eleven months later, in December 1877, an objection was raised to the renewal of John Thomas’s publican licence on the grounds that the hotel was in a dilapidated condition and had insufficient accommodation.[12] The case was adjourned until 28 December 1877, by which time an inspection was to have been made. The licence was granted, but Thomas may have decided that he’d had enough, as he left the hotel in June 1878.

The incident involving O’Meara was merely a fine of 20s plus 10s in costs, which was levied by the licensing bench for having drunken persons on the premises.[13] O’Meara left shortly afterwards, and the licence was transferred to William Gordon, who was there for about a year to 1890. He was followed by John Noonan, who was the Royal Oak’s publican from 1890 to 1891. John Nicholls went in on 21 May 1891 and left on 22 February 1892. After Nicholls came John Adamthwaite from 23 February 1892 until 14 May 1895 and John Noonan came back again as the licensee from 15 May 1895 to 3 December 1900. Alexander McDonald followed Noonan but he was only there for seven months, from 4 December 1900 until 2 July 1901.

By the turn of the century the ‘pub’ had become part of Australia’s cultural iconography, encompassing an idealisation of the bush and the bushworker. Familiar constructs of mateship and typecasts of ‘larrikinism’ embodied in the practices of ‘skolling’ and ‘shouting’ came to be seen as characteristic of Australian male identity and much of this was centred on the local pub. Like the British tradition from which it emerged, the concept of the corner hotel catering to its nearby residents and/or workers, and accessible by foot, was realised in the early settlement of Victoria, and was strongly entrenched among gold seekers and other workmen in Ballarat.

Temperance in Ballarat

The common practice among men from Ballarat and elsewhere of proving themselves in front of their peers by exhibiting a tolerance for alcohol gave rise to concern in the community. This was often expressed through the temperance movement, because the habit was felt to be detrimental to the interests of wives and families. Numerous missionary societies, the Salvation Army, the Australian Natives Association and the Protestant churches, often spearheaded by ladies’ auxiliaries and coming to include suffragette groups, raised the issue on all platforms available to them.

According to historian Peter Mansfield, the temperance movement failed because it came to be confused with ‘teetotalism’, meaning abstention, rather than moderate consumption. While the movement won the moral high ground, it lost the support of the great majority of people who enjoyed alcoholic drinks in moderation.[14]

During the height of the gold rush, temperance advocates had stressed that public drunkenness was a particular problem in country areas where there were too many sly grog shops, most of them said to be avoiding the payment of taxes and duties, as well as ruining family life and destroying the health of many young men.[15] When it is considered that one of the most popular home brews was called ‘Blow my skull off’ and another ‘Strip me down naked’, the ready availability of ‘sly grog’ probably justified the fears of temperance advocates. ‘Among the ingredients of “Blow my skull off” were spirits of wine, Turkey opium, rum, cayenne pepper, and water. After a few slugs of this formidable potion, a miner did not know whether he was in Ballarat or Bombay’.[16]

The substantial reduction of hotel licence fees to £25 in 1857 was a factor that contributed to the mushroom growth of drinking shops. Early in 1860 the Victorian Government announced that it would inquire into all aspects of hotel licensing laws with the object of reducing the number of licences issued. This caused a flurry of activity in Ballarat where licensed hoteliers were called upon to help fight the legislation. The report of the Select Committee found that there was a strong link between crime and anti-social behaviour, and because it was felt that neither the parliament nor the police could stop sly grogging, it was proposed that no new licence should be granted if one-third of the neighbouring population appealed against it.

In 1870, Ballarat experienced a period of depression, which affected every section of the community and many hotels closed down. At the end of that decade, only 250 public houses remained in the district, being a decrease of 50% in ten years.[17] Despite this reduction in hotels, public drunkenness remained a problem for many people and it was commented on in an article published by the Miners Weekly:

From what we remarked in the course of only ten minutes walk along the Main Road on Monday, it would seem that the vice of drunkenness is by no means on the wane in Ballarat. Attracted by a crowd at the United States Hotel, we went up and saw, between the hotel and the adjoining store, a space of not more than twelve inches in width, a woman in a helpless state of drunkenness, her legs twisted under her, her face flattened against the store wall, her arms upraised, and the crowd hooting and yelling. A little below the Charlie Napier, people were at their doors gazing at a respectably dressed woman reeling to and fro, and narrowly avoiding a jeweller’s window nearby. Near the John O’Groat were two men, arm in arm, both drunk, and drifting from side to side, while wagons carts and drays actually blocked the way. Not far from Sweeney’s Auction Mart were two drunkards, stock still in the centre of the road, leaning on the other. A few yards farther on were two men reeling about, and hallooing at every passer by. Verily there is plenty of room for the efforts of temperance reformers.[18]

By the 1880s the temperance movement had become very strong and associations were formed in every centre to energise a cause that demanded reduction of liquor licences and more stringent control of the liquor traffic. In Ballarat East, where there were 72 hotels, the temperance movement advocated reducing this number to 27 and a poll of registered electors was taken on 23 March 1888 to determine the number of hotels desired by each elector. The results disclosed that 995 votes were cast for 27 hotels and 590 votes for the retention of 72 hotels. There was a range of preferences for numbers between these two and 86 votes were informal, with one voter favouring 5,000 hotels! The Licensing Court decided that 45 hotels were to be deprived of their licences but one of the affected publicans lodged an objection on the grounds of irregularities in the appointment of the returning officer. His appeal was upheld and the poll was declared to be invalid and void.

Another poll was held in 1891 in Ballarat East where the licensed hotels now numbered 68. The outcome was problematic and a compromise was arrived at where the hotelkeepers agreed to the retention of 50 licences. Application was immediately made to test opinion in Ballarat West Licensing District, where 116 hotels were licensed in an area in which 41 constituted the statutory number. A keen and bitter contest was fought. Rowdy crowds interrupted the open-air temperance meetings and arrests were made of those throwing missiles at the speakers. The publicans again adopted a policy of modified reduction by concentrating on the retention of 90 hotels. By a process of elimination the election was determined to have favoured the retention of 90 licences, and in sittings commenced in March 1892 the 26 hotels to be delicensed were considered, with judgement delivered on the seventeenth of the month.

The Licensing Act was subsequently amended by investing a board with the authority to cancel the renewal of an existing licence, to award compensation to those affected, and the power to grant additional licences upon reasonable justification. The Licensing Reduction Board, which was established in 1906, had closed 19 hotels in Ballarat East and 47 in the West. Only 57 public houses remained under the control of the City Council, being nine less than the minimum desired by the temperance reformers fifty years earlier.[19] The Royal Oak was not delicensed, probably because it was by then tied to the Ballarat Brewing Company, which had made an effort to improve standards and encourage support for sporting, charitable and neighbourhood activities.

The Ballarat Brewing Company

On 12 January 1901 the Royal Oak Hotel was purchased from John Noonan by brewing partners William Tulloch and James Coghlan, directors of Ballarat Brewing Company Ltd, for the sum of £1200, and it is probable that Tulloch and Coghlan influenced the selection of licensees who followed McDonald.

The first of these was Ellen Jenkins, who was the Royal Oak’s publican from 3 July 1901 to 7 January 1902. Then came Frederick George Moore, who was there for sixteen months from 8 January 1902 to 5 May 1903. Moore was replaced by John Black for six months from 6 May 1903 until 10 November 1903, and he was followed by Bridget Kane, who was there from 11 November 1903 until 14 March 1912. Kane was selected over two competitors, the aforementioned Frederick George Moore and John Black.

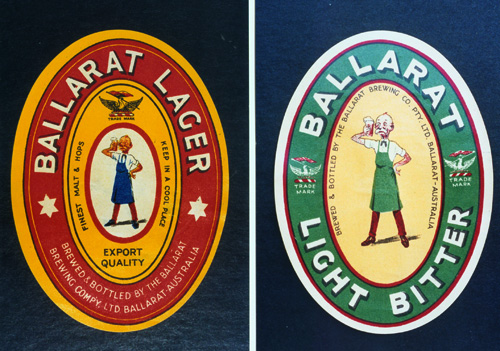

Coghlan and Tulloch’s Ballarat Brewing Co Ltd, originally formed to amalgamate brewing and hotel interests in Ballarat owned by Phoenix Brewing of Magill and Coghlan, and Royal Standard Brewery of William Tulloch and Son, was registered in Victoria in 1895. Both the Phoenix and the Royal Standard Breweries operated until 1911 when the Phoenix Brewery was closed.[20] In 1911 the company name was changed to Ballarat Brewing Co. Pty Ltd and reconverted to a public company under the name The Ballarat Brewing Company Limited in 1936.

By 1903 the Royal Oak was listed as number 46 in South Street and the adjacent mineshaft had been fenced off. The land next door was recorded in the rate book as having a frontage to South Street that measured 200 ft or 60.9 metres, and the owner of the land was listed as the New Kohinoor. The association between the Great Eastern Company and the New Kohinoor Company is obscure, but by the turn of the century the Great Eastern shaft was known as the North Kohinoor Shaft.

Image courtesy John Turner.

The New Kohinoor also ceased operations in 1911 and this may have precipitated a change in patronage at the Royal Oak concomitant with a general concern by Ballarat Brewing Company for higher standards of public decorum and sobriety. From 1903 right up to 1926, when the Royal Oak was leased to the Jermyn family, there had been only two long-serving publicans at the hotel: Bridget Kane, who took over from 11 November 1903 until 14 March 1912, and Margaret Guelpa, who married and changed her name to Margaret Allen, and was the licensee from 15 March 1912 until 6 February 1926. On 22 February 1926 the licence was transferred to John E Jermyn who had come to the Royal Oak from the Globe Hotel. Female licensees had been no guarantee of good behaviour among patrons and public opinion ran in favour of temperance and family influence in neighbourhood pubs.

Methodists and the temperance movement

On Tuesday 28 January 1890 the foundation stone of the United Methodists Free Church in South Street was laid. According to the report in the Courier[21] the old wooden building had been found inadequate to meet the requirements of an increasing congregation. The new building was to measure 33 x 54 ft or 10 x 16 metres, with an attached vestry, and have a seating capacity of 400. The number of church members was 102 with an additional 12 ‘on trial’. There were 17 Sunday School teachers and 200 scholars. The Rev. JB Johnson made a speech at the laying of the foundation stone, saying that God had prepared the work, for during the past twelve months there had been in excess of 100 conversions, and while the ordinary congregation crowded the church to the very doors, on special occasions scores and scores could not obtain admission. After the Reverend had spoken, the stone was declared well and truly laid by Edward Morey, who congratulated the committee and went on to say that the church would be right in the centre of a working population and that working people supported their churches. Morey then started a subscription on the stone.

Image Helen Dehn.

The Methodists were prominent among temperance advocates, and from their new church in South Street they may have viewed patrons of the Royal Oak and workers at the adjacent mine as a potentially rewarding challenge.

The Wesleyan church was sold to the Salvation Army in 1900, sold back to the Wesleyans in the mid-1980s[22] and finally sold for want of parishioners in 2008. There were close parallels between the philosophy of Wesleyan Methodists and that of the Salvation Army. Both groups, in addition to engaging in evangelism and practical missionary activities, held frequent open-air meetings, and both eschewed alcohol as well as dance halls and attendance at the theatre – all viewed as diversions from the family hearth.

Ballarat Bertie

A turning point in the ongoing tussle between the hotel trade and the temperance movement was reached in April 1926, with the launching of the Ballarat Bertie beer label featuring ‘Bertie the cellarman’. According to a report in the Courier, Bertie was born following discussions between the managing director of Ballarat Brewery, Mr Coghlan, and an anonymous advertising man he met on a train journey.[23] Max Harris and Peter Butters, however, have identified the advertising man as being from O’Brien Advertising, later Mooney Webb, and he was asked to create a character like ‘Johnnie Walker’.[24] Bertie was to become as iconic as Johnnie Walker and he came to be regarded with great affection in Ballarat. In 1971, after the Ballarat Brewing Company had been taken over by Carlton and United Breweries (CUB) in 1958, a decision was made to remove Bertie from the beer labels. A massive outcry over the removal of Bertie from CUB beer labels ensued. Ballarat Bertie was returned, only to disappear again when brewing at Ballarat ceased altogether in 1987. Ballarat Bertie was incorporated into the Ballarat APEX logo in 1988, and he became the mascot for the new warship, HMAS Ballarat, which was launched in 2002.

Bertie was first introduced in the Ballarat Courier on 24 April 1926 as a rather quaint little man whose only thoughts were focused on Ballarat Lager and Bitter.[25] He appeared weekly to begin with, drawn in different situations and confiding homespun tales to his drinking pals. On Saturday 1 May 1926 he appeared under the heading ‘Life has its tragedies’ in reference to having dropped and broken a bottle of beer. The copy reads: ‘bang goes more than a pint of enjoyment but a pint of sustenance that makes a gink feel he is boss of the roost instead of the missus. Every time I break a bottle of Ballarat I sort of feel that I have done the dirty to one of my pals’.[26] This was a wonderful campaign and it endeared Bertie to men of all classes and ages (and probably some women as well) although it was definitely aimed at Ballarat’s working-class men who, by the time of Bertie’s second appearance, were implied to be henpecked and were being enjoined to rule the roost.

Images courtesy John Turner.

Image courtesy John Turner.

Concomitant with the introduction and continuing appearances of Bertie, the Royal Oak ran its own campaign to soften the attitude of the general public towards drinking in hotels by installing a succession of licensees with families. John E Jermyn was the first licensee to reflect this more family-oriented policy. In 1919, John Jermyn was a grocer at 1009 Dana Street,[27] and he later ran a tearoom in Sturt Street. He may have continued one or both of these businesses because on 16 December 1929 he transferred his victualler’s licence at the Royal Oak to his wife, Margaret, at the same time as he applied for permission to sell and/or dispose of non-intoxicating liquor between 6.00 and 6.30 pm.[28] Permission to sell non-intoxicating beverages was granted by the Licensing Court on condition that John had no further involvement in running the hotel. John Jermyn took over at the Royal Oak on 22 February 1926 and continued until 15 December 1929. His wife, Margaret, held the licence at the Royal Oak from 16 December 1929 until 15 February 1931, and on 16 February 1931 the licence was again transferred, this time to John and Margaret’s daughter, Ellen Elizabeth (Nellie) Jermyn. Nellie held the licence through the war years until 30 June 1953.

Image courtesy John Turner.

The Jermyns were followed by the Pells, who came to the Royal Oak on 1 July 1953 and remained there until 1976. George Arthur Pell, his wife Margaret Lilian, and their three children, George, Margaret and David, all served behind the bar and were ably assisted by Margaret’s sister, Molly Burke, who lived with the family. George Pell Jnr was to become a Cardinal and his sister, Margaret, a violinist with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. David attended the School of Mines and did a lot to help in the hotel after his siblings left home and his mother had a heart attack.

The Pell years saw a club-like atmosphere develop at the Royal Oak where patrons were well known to each other. A Social Club was formed and members engaged in games of euchre, and ran hooky competitions between the Royal Oak and other hotels. The club held its own picnics at Burrumbeet and members competed in foot races, egg and spoon races and sack races. A barrel of beer was taken out to the picnic, which was paid for by the Social Club, and they also had a Christmas party for children every year with presents from Santa. On Christmas Day, when patrons went home for lunch, Margaret played the violin for her family. No accommodation was offered at the hotel, however, and nor were meals served to patrons. The bar was divided into three small rooms at this point, the middle room forming the bar itself, a room to one side with a heater in it, and a room on the Raglan Street side, which was rarely used.

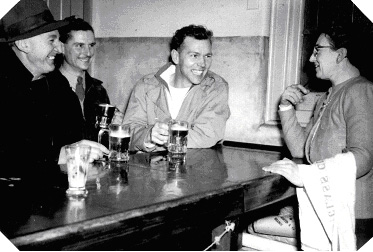

From 1976 to 1978, the licensees at the Royal Oak were Ian and Fay Baum, who instituted a lunch for 80 cents, and after the Baums came Bob and Ada Jelbart. The Jelbarts held the licence at the Royal Oak from 1978 until 1987 and became very popular during that time. As can be seen in the photograph below, entry to the bar was from a door on the right, which opened from the main entry door in South Street. Sporting trophies won by Social Club members can be seen lining the shelves, and the number of women in the bar, happily toasting farewell to the Jelbarts, is testament to the success of the family friendly policy, more fully developed during this period.

The Jelbarts were followed by Doug Penna and his wife, Jan, who held the licence from 19 January 1987 until 28 March 1988, and then came Adrian Patten and Shaun Duke, who were there for about twelve months from 1988 to 1990. Doug and Jan began the move towards making evening meals a feature of the Royal Oak, an initiative seized by Adrian and Shaun, particularly after Adrian married Shaun’s sister. People in the neighbourhood were encouraged to call in for evening meals as well as lunches, and a party atmosphere became the norm.

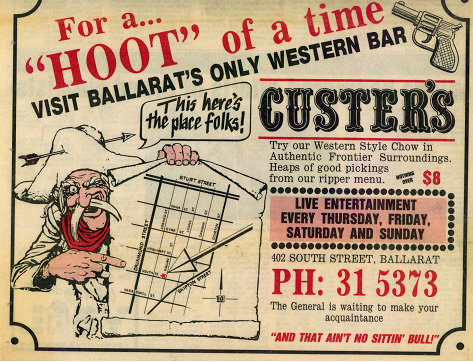

This set the stage for a licensee named Tasi Stampoultzis, who arrived with his family in 1990 and turned the Royal Oak into a Wild-West show, drawing on the American General Custer and his famous last stand. Stampoultzis covered the Royal Oak sign emblazoned in the hotel’s rendering with a metal wrap-around sign that read ‘Custer’s’ and advertised Western-style chow in authentic frontier surroundings. A report in The News in September 1991 described the atmosphere as follows:

Hewn timber beams, lintels, bows and arrows, muskets, wine barrel tables, tilley lamps, saddlery, General Custer cartoons and wanted posters set the scene for a rollicking good time. Permanently standing at one end of the hewn bar is General Custer himself (a fibreglass mannequin in full battle dress, fashioned by Ballarat artist Chris Pendlebury). Corrugated iron panelling and ‘Custer’ wallpaper…adds to the frontier feel. An open wood fire invites patrons to give up the comfort of their own homes and enjoy what Custer’s has to offer. The large L-shaped lounge has a saloon look: shuttered windows, a pool table and the open fire. A food servery with blackboard menu is located in the lounge, catering for both eat-in and take-away meals. Items consistent with the ‘Wild West’ theme include ‘prairie dogs’ (hot dogs with cheese and bacon and chilli sauce) and Custer burgers (prime beef or chicken breast burgers). Live entertainment featuring well-known bands is available at Custer’s every night from Thursday to Sunday. An extended beer garden is available for large outdoor functions.[29]

According to Stampoultzis, Custer’s was not like every other hotel and ‘we will give patrons better than they’ve got at home’.

Image courtesy John Turner.

Image courtesy John Turner.

The name Custer’s is still etched into the floorboards under the existing pool table, but the hotel has undergone such extensive restoration in the past thirteen years that no other trace of Custer remains. The neighbourhood had become used to a family-friendly hotel, so there was a sense of relief in May 1994 when Custer and the Wild-West left and the hotel was taken over by John and Karen Turner, who arrived together with their family. The Custer sign was removed from the front of the hotel and the Royal Oak sign restored to its former glory, much to the approval of neighbourhood patrons. Ballarat Bertie was also restored to pride of place above the bar where he still reminds patrons of his critical role in the promotion of Ballarat Bitter, along with community interests and values.

Image courtesy John Turner.

Meals could not be provided until the kitchen and bar had been renovated, so these areas were among the first to be attended to. Upon arrival there was no laundry, nothing upstairs and the kitchen had been closed. The new kitchen was opened early in July 1994 and the first meal served from it was part of a gala ceremony that was very well attended by workmen and locals. Once the outside areas had been brought to order, there were also functions held in the beer garden enjoyed by the hotel’s regular patrons.

Karen is still the honorary treasurer of the men’s and ladies’ darts teams, a post she has held since 1995. Darts teams compete in a competition organised by the Australian Hotels Association, but increasing transience among hotel licensees and the popularity of poker machines have contributed to a decline in darts team membership. The menu has been expanded with more main meals and more entrees, and a choice between salads or vegetables can be made from the buffet style servery. The Royal Oak has become very much a home away from home for many people in the neighbourhood, and John and Karen are both held in high esteem by their friends and regular patrons.

Image courtesy Karen Turner.

Conclusion

Today, there are over 50 pubs in Ballarat offering varied menus and entertainments, but central to a good pub is, and always has been, the publican who creates the atmosphere best suited to his patrons. These are now male and female, and they are intent, not on getting drunk or proving anything, but on enjoying well-prepared meals and convivial company. The Royal Oak is a traditional pub yet responsive to its environment and for these reasons it has become a valuable social asset.

Endnotes

[1] ‘Our “Public Houses” were born on the 1850s goldfields’, The News, Ballarat, 6 July 1989, p. 11.

[2] ‘Ballarat 1867’, Courier, Ballarat, 16 June 1967, supplement, p. 12.

[3] A rule of thumb for making very approximate conversions into today’s Australian dollars is: for 1850s pounds, multiply by 120; for 1900s pounds, multiply by 100. There were 20 shillings (symbol ‘s’) to the pound.

[4] Ballarat Rate Book 1858, PROV, VPRS 7259/P2 Rate Assessment Books, Unit 104, p. 239 (these records are held at the Ballarat Archives Centre).

[5] Star, Ballarat, 19 September 1866, p. 2.

[6] ‘House for Sale’, Star, Ballarat, 19 October 1866, p. 1.

[7] Ballarat Rate Book 1868, PROV, VPRS 7260/P1 Rate Assessment Books, Unit 5 (these records are held at the Ballarat Archives Centre).

[8] 1 link = 7.92 inches (or 20.1 cm); 100 links = 66 feet (or 20.1 m) = 1 chain.

[9] Frederick L Hunt, Ballarat: a golden past: a shining future: built on gold, Ballarat Art Gallery, 1992, see map located on the inside back cover; W Baragwanath (field geologist), Geological and Topographical Survey, Ballarat Goldfield, reference x-518/G/33, Victorian Department of Surveying, Melbourne, 1917.

[10] ‘Notes’, Evening Post, Ballarat, 24 January, 1877, p. 2.

[11] Inquests Index 1836–1888, Edward Mathew O’Brien, Ballarat 1877, Ref. 86.

[12] ‘City Licensing Court’, Courier, Ballarat, 19 December 1877, p. 3.

[13] ‘Licensing Bench’, Courier, Ballarat, 22 July 1877, p. 2.

[14] Peter Mansfield, ‘Alcohol flows freely’, Courier, Ballarat, 22 February 1990, p. 6.

[15] ibid.

[16] ‘Thirsty Days’, The News, Ballarat, 6 July 1989, p. 14.

[17] John Hargreaves (ed.), Ballarat hotels past and present, privately printed, Ballarat, 1943, p. 5.

[18] ‘A stern view of intemperance’, Miner’s Weekly, 15 August 1886, republished in The News, Ballarat, 6 July 1989, p. 14.

[19] ibid. pp. 6–10.

[20] Steve Deaville, ‘The Ballarat Brewing Company Limited’, Victorian Beer Label Collectors’ Society Newsletter, vol. 7, no. 1, February 1978, p. 3.

[21] ‘United Methodist Free Church, South Street: laying the foundation stone’, Courier, Ballarat, 29 January 1890, p. 4.

[22] Nick Higgins, ‘The possibilities are endless, just use your imagination’, Courier, Home Magazine, 24 September 2007, p. 12.

[23] Peter Barnes, ‘Story of Bertie’s Ballarat Bitter’, Courier, Ballarat, 30 August 1980.

[24] Max Harris and Peter Butters, Recollections: 20th Century Ballarat, Max Harris, Ballarat, 2003, p. 10.

[25] ‘Introducing Bertie the Cellarman’, Courier, Ballarat, 24 April 1926, p. 11.

[26] ‘Life has its tragedies’, Courier, Ballarat, 1 May 1926, p. 9.

[27] Australian Electoral Commision, Electoral Roll, Division of Ballarat, 1919, available at http://www.ancestry.com.au, accessed 8 October 2009 (only available to subscribers).

[28] PROV, VPRS 719/P24>, Licensing Register, p. 57 (these records are held at the Ballarat Archives Centre).

[29] ‘Custer’s: great place for a stand’, The News, Ballarat, 26 September 1991, p. 24.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples