Last updated:

‘The Curious Case of the Wollaston Affair’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 7, 2008. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Lyn Payne.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Edward George Wollaston was born in South Australia in 1857 and died at Murrumbeena in 1935. His life spanned decades of educational change in Victoria, when National and Denominational schools were brought together under the Common Schools Act of 1862; education became free, compulsory and secular through the Education Act of 1872; and the 1883 Public Service Act gave teachers the status of public servants. Wollaston’s career provides an insight into the personal consequences of these measures that formalised methods of appointment and promotion, and saw seniority and merit become the basis for advancement rather than family connections or political patronage. His story is that of one individual’s encounter with an intransigent administration, rigid bureaucratic procedures, political expediency and a system that demanded unquestioning compliance. It also demonstrates Edward’s own persistence and determination, his various strengths and foibles as a teacher and, most importantly, his ongoing quest for official redress of a perceived injustice, a case that became known as the ‘Wollaston Affair’. An honourable man from a religious family, Edward was fined £5 and severely censured by Duncan Gillies, Minister of Public Instruction, in 1884. An indelible mark was put against his career and still exists in his files. For forty years he tried to clear his name, and, in so doing, engaged in a dispute with the Department of Education that was firmly grounded in contemporary debates and, in particular, in the contested area of state education and religion.

Edward George Wollaston came from a family of churchmen and educators. He was named for his great-grandfather, Edward Wollaston, who was master at Charterhouse School, London where his maternal great-grandfather, Dr Ramsden was headmaster. Edward’s grandfather, John Ramsden Wollaston, was educated at Charterhouse and Christ College, Cambridge where he took his degree and was ordained. He married Mary Amelia Gledstanes and they produced a family of five sons and two daughters. Edward’s father was their fourth son, George Gledstanes Wollaston.[1]

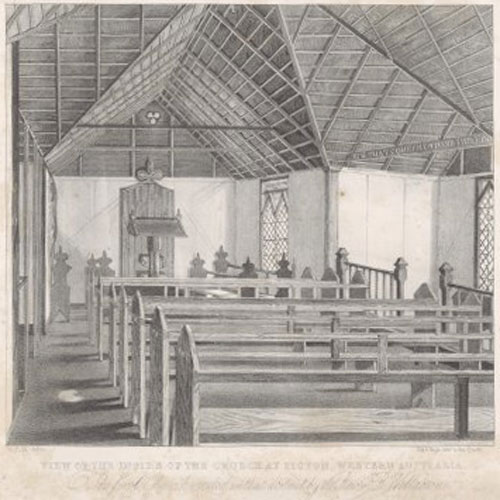

To support their growing family, John and Mary migrated to Western Australia where John was promised a ministry at a proposed new settlement on Port Leschenault. On arrival, however, he was dismayed to find he had to construct his own church before receiving any wages. He and his sons set about building a small wooden church with a thatched roof, which was consecrated in 1842. Colonial life suited John, and his personal qualities and dedication to missionary work led him to remain in the West where he became Archdeacon of Western Australia, an office he held until his death. His sons, George, Henry and William, moved on to South Australia where George, a religious man of resolute faith, became manager of Poonindie Aboriginal Mission. He later travelled through South Australia and Tasmania, visiting influential acquaintances with letters of introduction from his father. He married Mary McGowan, daughter of the Reverend James McGowan, who ran the first classical school in Adelaide. Their first son, Edward George, was born at Gum Creek on 3 October 1857. In 1860 George became manager of Lake Hamilton Station near Port Lincoln, where Edward spent his childhood.[2]

National Library of Australia, GM Matthews collection of portraits of ornithologists 1900-1949, ID 3799374.

Edward’s early education was at Whinham College in Adelaide but at the age of eight he was sent to Victoria where he remained for the rest of his life. He lived with his Uncle Henry who had become Minister of Trinity Church on the corner of Hoddle and Hotham Streets and he attended the attached Denominational school that later became State School 303, Hoddle Street, East Melbourne. In 1873 Edward was appointed pupil-teacher under the head master Stephen Trythall and two important strands of his life, pedagogy and religious commitment, were established.[3]

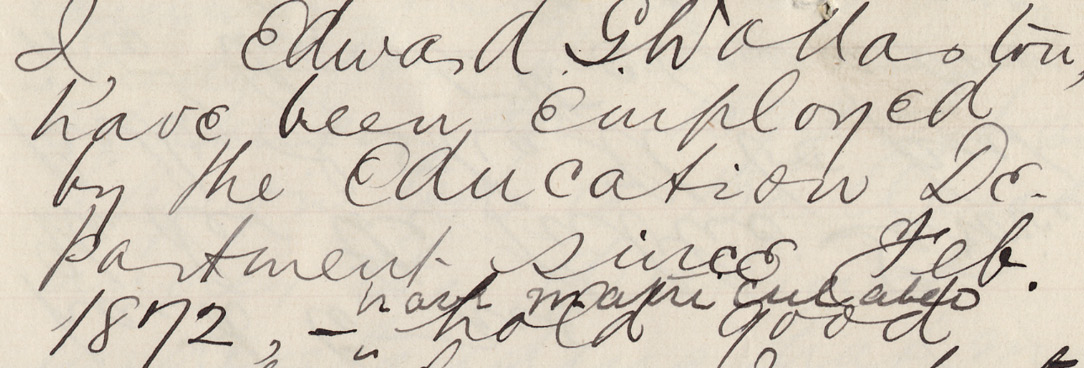

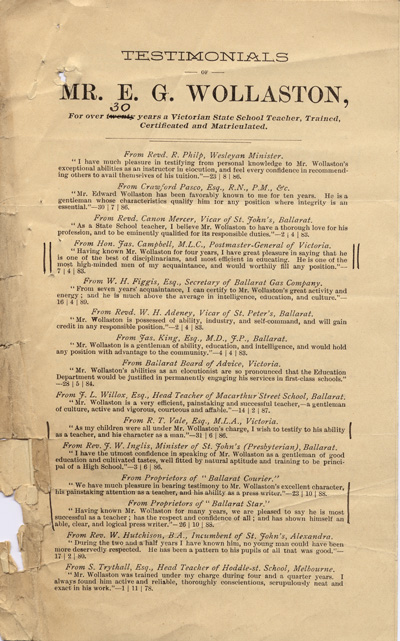

The pupil-teacher system was a method of teacher training designed to provide staff to the growing number of state schools under the jurisdiction of the Department of Education. Edward’s acceptance of a pupil teachership indicates that his family thought this a useful career and one that would enable him to proceed to higher education. Edward was ambitious and diligent in following this path. As a pupil-teacher he was efficient and obedient. In 1878 he was praised by head teacher Stephen Trythall: ‘Mr Wollaston was trained under my charge during four and a quarter years. I always found him active and reliable, thoroughly conscientious, scrupulously neat and exact in his work’.[4] Having gained his Licence to Teach, Edward wrote to the Department of his ambitious plan to matriculate and continue on to a university degree.[5]

National Library of Australia, ID 7748222.

Mary Davies Barker commenced duty at Alexandra State School 912 in 1873, the same year that Wollaston was appointed pupil-teacher. Mary was born in Devonshire around 1843 and was about nine years old when her family travelled to Australia.[6] They settled in Sandhurst where her father, Charles Eli Barker, was a land surveyor. Mary commenced employment as a teacher in 1867 at the Church of England School, New Gisborne but was dismissed from her position when deemed to be ‘a female teacher not being equal to the growing requirements of the school’.[7] She later took up employment with the new Department of Education at Alexandra State School 912. Her records show she was frequently absent for long periods, her health already affecting her ability to work. Inspectors Main and Gamble considered her ‘Moderate in ability but lacks energy’ and Inspector Craig thought she ‘has skill – lacks life’.[8] In April 1877 Mary was joined on the staff by the young, bright and ambitious second assistant, Edward George Wollaston. Edward was then twenty years old and Mary about thirty-five and most certainly frail in health.

In August 1877 a confident Edward requested a transfer to a larger centre at either Ballarat or Melbourne where he could pursue his studies for a university degree. In November he wrote again to the Department, stating his need for time for study. By December he had passed the literary section of his Certificate examination and again applied for transfer to Ballarat. Almost a year passed. By October 1878 he was fearful he would lose his position at Alexandra due to falling attendances. He did not want his career stalled through transfer to a small bush school and again pleaded his case for removal to a city where he could pursue his studies. ‘I respectfully beg that I may be transferred to Ballarat or another of the large centres,’ he wrote, ‘where I may have a better opportunity of making myself efficient in the higher branches of learning than I possess here.’[9]

Edward and Mary were distressed when the school was examined in November 1878 and they each received a poor report from Inspector Gamble. Mary, as noted above, was described as ‘moderate in ability’, but Edward received the devastating judgement of ‘poor’.[10] Fearing the report would have a prejudicial effect on their careers, they worked together on a reply. ‘We respectfully beg that the adverse report of Mr. Gamble may not affect our credit in the department’, they wrote. Epidemics had swept through Alexandra and obviously affected their results. In addition they thought the examination ‘was unusually severe’. The letter is written in Edward’s hand and he attached several testimonials, a strategy he practised throughout his career. In 1878 these were copied carefully in his hand, but later his testimonials were published in a brochure that he affixed to appropriate letters.[11] Edward would use Trythall’s ‘much superior to the generality of junior teachers’ and Inspector Main’s ‘active and skilful in the discharge of his duties’ as testimonials for the next thirty years.

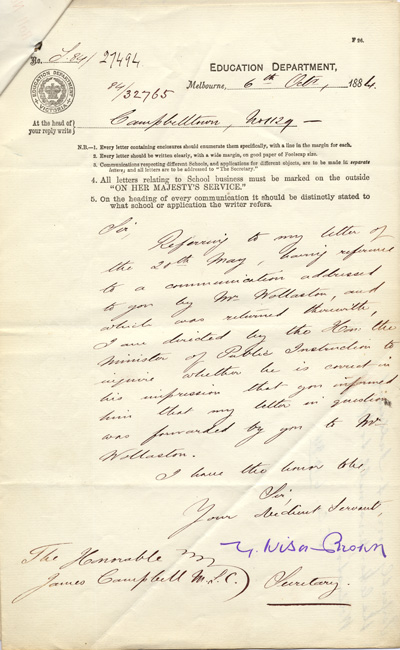

PROV, VPRS 892/P0, Unit 84, Special Case 894.

Edward often impatiently avoided bureaucratic procedures and appealed directly to ministers; or he utilised his excellent contacts to do so on his behalf. In December 1878 his maternal uncle, JT McGowan, a chemist and druggist of Ballarat, intervened with a letter to the Hon. Major Smith, Minister of Public Instruction, noting that Edward was an exceedingly good cricketer and would be most useful to the Ballarat Cricket Club.[12] In June the following year, McGowan received a guarantee that Edward’s transfer would occur when convenient. In July 1879, Edward wrote to the Department restating his ambitions for a university career. Typically he had taken his case to a higher authority: ‘During the Easter vacation I had a personal interview with the Inspector General who kindly made a special note of my case’.[13] His Uncle Henry wrote to the Department and made a personal visit, while McGowan petitioned Henry Bell, Member for Ballarat West: ‘If you would use your influence for me on this occasion with the Major at the Department, I should be very much obliged to you.’[14] By August 1879, McGowan noted that he had been asking for a transfer for his nephew for two years and received the reassuring reply that special consideration would apply. In September, Edward’s insistence and his family’s interventions finally succeeded in an offer from the Department of a position as fifth assistant at State School 2022, MacArthur Street, Ballarat.[15] Edward was ‘chosen’ from eleven applicants but in fact he paid a heavy price for this transfer. He was overqualified for the position (most of his competitors for the position were pupil-teachers), he accepted a demotion to fifth assistant and, unknown to him at the time, the transfer meant a considerable reduction in salary.

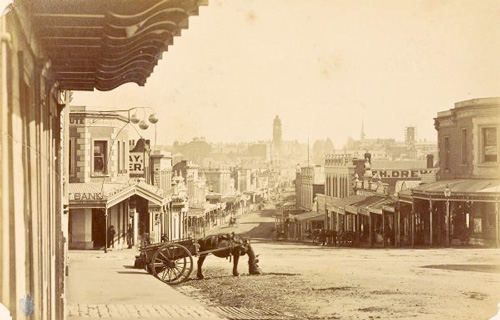

National Library of Australia, album of photographs from the private library of H Grattan-Guinness, ID 3084147.

In September 1879, however, Edward looked forward to university studies, graduation, and a rising career. On the evening of 1 October, he and Mary married, took the next day for a honeymoon and returned to school on 3 October. Head teacher Charles Cookson slipped his letter informing the Department of their marriage into a drawer and promptly forgot about it. On 2 October, in an optimistic mood, Wollaston wrote to the Department requesting that his wife be transferred with him to Ballarat or, failing that, to Sandhurst, where her father resided. In the meantime, he made plans to attend his matriculation examination in December: ‘If the Department can conveniently remove me soon, I intend paying for the first year’s university course’. After bureaucratic delays, Edward finally left for Ballarat on Saturday, 8 November with the problem of Mary’s transfer unresolved. Despite numerous pleas to an unyielding Department, she remained ill and alone at Alexandra for another nine months.

Tragically, Edward’s plans for their future together began to unravel. After Mary requested two days’ leave to obtain specialist medical advice in Melbourne, her husband advised the Department that she would resign her position due to ‘a complaint beyond remedy’. A doctor’s certificate identified Mary’s illness as a large fibrous tumour of the womb, which was considered incurable but could be alleviated through rest. Faced with medical expenses and a single salary, Edward asked to remain in his present position and await promotion. Mary retired from the teaching service on 30 June and joined her husband at their residence in Lydiard Street, Ballarat.

Edward was only twenty-three years old while Mary was in her late thirties. He now found himself in Ballarat in a reduced position on a diminished salary with a wife not only in frail health but possibly mortally ill. He begged the Department to compensate his salary to its previous amount, maintaining that he had not realised his new position would result in a lower classification and lower wages. The Minister agreed to a special supplement that ceased on 1 July 1880 when such payments were cut. More seriously, due to impending legislative change, Edward’s straitened circumstances threatened to become permanent. The implications of the imminent Public Service Act, the role of the Committee of Classifiers and the effect of ‘Classification on present positions’ concerned him deeply. He knew that without immediate promotion he would be permanently classified in the 5th class with a salary of £116, ‘while many of my equals and juniors go into the 4th or 3rd classes … simply because their present positions are higher than mine’. He requested that his case be put on a Department list of ‘hard cases’, ‘as my claim to go into a higher class can only under such circumstances be investigated by the Classifiers who otherwise have no power to do so’.[16]

PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 153, Ballarat State School 2022, received 15 November 1883.

Edward’s only other opportunity for an improved position was an immediate promotion to head teacher before the Public Service Act came into effect. For this to occur he had to obtain a first-class certificate of competency that included his ability to draw up a timetable. To pass this certificate, his timetable had to be inspected while in operation, and inspection could only be implemented if he was a head teacher in another school. Again his Uncle Henry intervened to secure an improved position for his nephew. Reverend Wollaston used his influence and political connections to prompt the Minister of Public Instruction to find Edward a temporary head teachership at a small country school. For Edward, this was a welcome change of luck. The year 1883 was not kind to his family. Mary’s brother died in January and it is likely they also lost their first daughter, Ruby May, around this time. Moreover, his family was growing. Despite her illness, Mary was already pregnant with another child, Mary Beatrice, who was born in January 1884. They were to have another daughter, Frances Amy, born in 1886. Frances had a physical ailment, probably spinal, that required her to lie upon a sloping board at intervals during the day.[17]

By early 1884 Campbelltown State School 1129 had had four head teachers in four months due to its remote location and the poor condition of its teacher’s residence, but for Edward it offered promotion and opportunity. With a confident flourish, he accepted the Department’s offer of temporary head teacher. Over Easter, he and Mary, with four-month-old Mary Beatrice, packed their belongings in anticipation of their move. To their dismay, they were met with filthy conditions, scratched, stained and greasy walls, broken windows and a leaking tank. Cleaners had to be put to work to make the school and premises habitable in order to accommodate his family.[18]

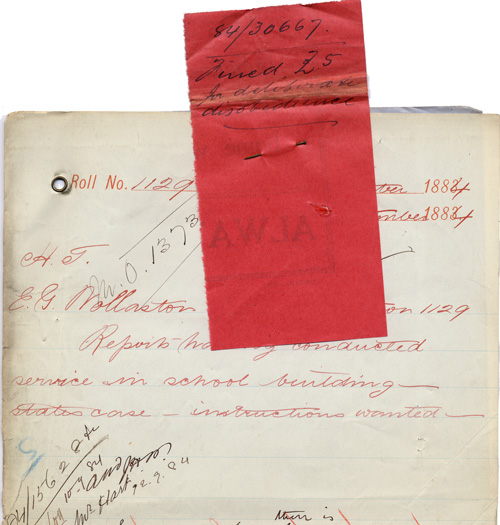

Worse, for Wollaston, Campbelltown 1129 would become a testing ground for some of the thorny issues of the day: the relationship of church and state; the provision of secular education; the rights of teachers under the 1872 Act, the intrusion of government bureaucracy in the lives of its employees; political loyalty, expediency and, perhaps, dishonesty. Edward’s elation at promotion soon gave way to a desperate bid to save his name and erase a serious charge against him, a charge that to this day is marked by a bright and unmistakeable red tag in his file. Years later, Charles Long was to write of Wollaston as having ‘a unique place in the history of education in Victoria as the teacher who was fined £5 for conducting a church service in his school’.[19] The unlikely labels of ‘insubordination’ and ‘distinct insolence’ are still written in Edward’s file in Departmental red crayon.[20]

It is doubtful whether, with his deeply religious Anglican background, Edward ever fully concurred with the provisions of the 1872 Education Act, particularly that section which stated that ‘secular instruction only shall be given’, and ‘no teacher shall give any other than secular instruction in a State school building’. His father thought compulsory education was a radical plan to educate Catholic Irish ‘peasant children’ in order to ‘put them on an equal footing with the most refined “Jack” in this colony …’.[21] As a newly appointed head teacher, however, Edward was compelled to act within the 1872 Act’s parameters and took his duties seriously, both to the Department and to his own school community. Within weeks of arrival he was approached by residents of Campbelltown who wished their children to attend Sunday School classes. As the school building was the only public building available, Edward was asked to contact the school’s Board of Advice for permission. Following the correct procedure, he wrote to JN Pritchard, Correspondent, and offered his own assistance to ‘guarantee preservation of furniture etc.’. Inadvertently he addressed this letter not to the Board of Advice but to the Department of Education and it landed on the Secretary’s desk. Mistaking Edward’s offer of help to be potentially one of personal supervision of the Sunday School class, the Department curtly reminded him that Section 12 of the 1872 Act precluded him from giving religious instruction in state schools and that he therefore was not permitted to provide assistance to Sunday classes in the Campbelltown school building.[22]

Edward was incredulous. First he chided the Department for responding to a letter clearly intended for the Board of Advice: ‘I regret the mistake the more in that, from the tenor of your letter, it would appear that the fact was overlooked that I was addressing the correspondent of the Board of Advice’.[23] Then he applied for further information on the Department’s interpretation of the 1872 Act. In his view, the Department’s position was a ‘strained’ one. He was aware of the section relating to religious instruction in state schools but he did not know that ‘such a strict interpretation could be made’. Weren’t teachers free on Sundays from their responsibilities as employees of the Department? Were state school teachers barred ‘from religious liberty outside of, as well as within, the hours in which they were in the employ of the State?’ In the absence of this knowledge, he said he had already taught Sunday School in state school buildings for the last six years, as had scores of other teachers throughout the colony. He went on to inform the Secretary that he had already made contact with Mr Duncan Gillies, Minister of Public Instruction, had laid the whole matter before him, and was awaiting his advice. A stern reply from the Secretary instructed him to correspond through the proper channels and advised that the Minister entirely concurred with his own Department’s view. There was no ‘strained interpretation of the Act’ involved; and their advice simply gave effect to the deliberate intention of the legislature as it was passed by the Parliament.[24] For the time being, Edward obeyed his instructions. He taught Sunday School, not in his own school but at nearby Glendower Station, walking two miles each Sunday to bring the gospel to the children. The matter might have rested there, but two events occurred that together set in motion a chain of events that became known as the ‘Wollaston Case’. Edward wrote a letter; and a visiting preacher was ill.

In May 1884, Edward wrote a private letter expressing his thoughts on religious instruction in schools to his friend, the Honourable James Campbell MLC, Postmaster General and a prominent Methodist with business connections to Ballarat. Knowing from past discussions with Campbell that their opinions were identical, it is likely Edward was extremely frank in his views. Both men probably agreed that Bible reading would inevitably be reintroduced as part of the state school curriculum. Years later, in a letter to the Ballarat Courier, Wollaston enthusiastically supported the introduction of Bible reading into schools by teachers ‘who daily feel that our earnest endeavors at turning out good men and women are sadly crippled and hampered by our inability to go to the Scriptures for both authority and example’.[25] Edward was keen to enlist Campbell’s help in obtaining the true thoughts of Minister Gillies on the subject of religious instruction in state schools and he invited Campbell to add any ideas of his own that might be useful. However, Campbell proved most unhelpful in advancing Edward’s case. Inexplicably, ‘by some unaccountable error of judgement’,[26] or perhaps because he wished to draw Wollaston’s well-drawn arguments to the Department’s attention, he simply passed Edward’s letter on to G Wilson Brown, Secretary of the Department, who in turn submitted it to the Minister. As one politician to another, Gillies courteously replied to Campbell: ‘There is no objection to Mr Wollaston conducting a Sunday school or Church service [author’s italics] provided that the meetings are not held in a State school building’.[27] This letter, with Edward’s private correspondence attached, was then returned to Campbell. There is no written evidence that the Minister or the Secretary instructed Campbell to pass this advice on to Wollaston. If there was any arrangement between the two politicians, and it seems there was, it must have been verbal. All official correspondence from the Department to Wollaston refers only to the ban on religious instruction by Departmental employees in state school buildings. The Minister’s letter to Campbell is the only time the phrase ‘or Church service’ appears in their correspondence, a point vital to understanding the following damaging events.

The residents of Campbelltown continued their quest for religious worship on Sundays. Over the next three months, correspondence took place between John Pritchard, Correspondent for the Board of Advice, and the Department of Education, requesting permission for the Reverend Bettus, a Bible Christian Minister based in Clunes, to conduct public worship and Sunday classes each alternate Sunday in the Campbelltown State School building. Edward Wollaston, as head teacher, was informed of this decision and helpfully wrote to the Department to inform them that Reverend Bettus had commenced his Sunday services on 31 August 1884. Further, he went on, on the previous Sunday, 7 September, he had had to take the service himself, for ‘neither that gentleman nor his assistant appeared at the appointed hour. In consequence of this, I was urgently solicited by the congregation to officiate. I undertook the responsibility and now take the first opportunity of reporting the matter to the Department’. While he had been prohibited from giving religious instruction, he continued, he was anxious to know if officiating at a church service was within Departmental guidelines. ‘I am desirous of knowing if, in conducting Divine Worship, I am acting with the consent of the Department’.[28]

On receipt of this letter and in the light of his previous advice to Wollaston, Minister Gillies erupted! ‘The law on the subject which was already sufficiently clear to so many persons has been specially explained to Mr Wollaston. He shouldn’t act in violation of it and should be fined therefore. … Any repetition of the offence will be visited with suspension from duty.’[29] Wilson Brown was directed to write the censure to Wollaston:

I am directed by the Honorable, the Minister of Public Instruction to whom your communication has been submitted to inform you that he regards this question as a piece of distinct insolence and he has decided to inflict a fine of Five Pounds (£5) for your deliberate disobedience of instructions.[30]

Edward was shocked. To him, the prohibition on religious instruction of children, which was at the heart of the drafting of the Education Act, did not include divine worship for families. He had reported his actions to the Department in order to seek Ministerial guidance; he had not willingly reported himself for deliberate disobedience! ‘The Minister is in error in supposing that I have been guilty of “deliberate disobedience to instructions” in conducting Divine Worship as I had received no instructions on the subject’, he replied.[31] As he wrote, he noted that the Department’s instructions of 16 May lay open in front of him on his desk. The letter only referred to religious instruction, ‘and the offence for which I am to be fined lies in the fact that I acted in an unforeseen emergency in the absence of instruction’.

Gillies was exasperated. He could not believe that Wollaston had any doubt that the prohibition on religious instruction included divine worship. ‘It is absurd to suppose that Mr Wollaston has any serious doubt whether conducting Divine Worship is included under that term’, he wrote. Not so, Edward answered. ‘In reply I can but repeat my assurance that I had no idea that my action was contrary to law, nor that Divine Worship had any connection with religious instruction.’ Astonishingly, the Department then directed Edward’s attention, not to its own correspondence with him, but to their letter addressed to James Campbell, ‘which we understand was forwarded to and received by him [i.e. Wollaston].’ In this letter, Gillies clearly set out the Department’s interpretation of the 12th Section of the Act, and the Minister was therefore at a loss to understand how Wollaston could still claim that he acted in ignorance. To ensure Edward was fully aware of the contents of the Campbell letter, the Department attached a copy. At the same time, Wilson Brown approached Campbell to ensure that he had forwarded the Minister’s letter of 20 May to Wollaston. ‘Perfectly correct’, Campbell scrawled across one corner, ‘I addressed the letter personally to Mr Wollaston.’ Campbell also took the liberty of informing Edward Wollaston of Cabinet discussions in which it emerged that Gillies had acted without consultation, that Premier Service endorsed the view that Wollaston should have had opportunity to defend himself, and that a majority of the government were opposed to Gillies’s actions.

PROV, VPRS 892/P0, Unit 84, Special Case 894.

Edward was prompt and honest in his reply. He acknowledged that he had received the copy of the Department’s letter to Campbell with his own, private correspondence to Campbell attached. He admitted that he had earlier enlisted Campbell to obtain, as one politician to another, a personal opinion from Gillies on the 12th Section of the Act. Campbell had indeed forwarded a letter addressed to himself and signed by the Secretary and had added a personal note that ‘he had not had time to look up the Act in order to endorse (or otherwise) the opinion of the Minister’. Unfortunately Edward was unable to find these letters amongst his personal papers. However, he maintained that the words ‘or Church service’, which appeared in the Campbell letter, were either omitted from the copy received by him, or overlooked by himself, his wife, and the work mistress at the school, all of whom had closely examined the correspondence. Again the Minister erupted. Rather than serving as an explanation, Edward’s words were considered inflammatory, a further deliberate insult to the Minister. He was directed to withdraw his assertion that ‘Church service’ was omitted from his copy of the Campbell letter, for this was an imputation upon the credit of the Department. Edward responded immediately. He was dismayed that his own admission formed the basis of the Department’s case against him of deliberate disobedience. He admitted that he had been instructed not to take religious instruction but he had conducted divine worship in the school building owing to the illness of the regular preacher. He maintained, correctly, that he had no official access to the correspondence of the Postmaster General, and no letter addressed directly to him by the Department ever included the words ‘Church service’. Moreover, as the significant letter was personally addressed to Campbell, it is quite likely that Wollaston did not directly connect the phrase to himself, or to any actions that he would take three months into the future.

The matter was not allowed to rest. On 23 September a petition in support of Wollaston, signed by the residents of Campbelltown, was sent to the Minister. The petitioners asked for remission of the imposed fine and protested that Mr Wollaston only consented to conduct divine worship at their earnest request as the officiating minister had failed to arrive.[32] They were informed unsympathetically that in view of the importance of maintaining proper discipline in the Department the Minister felt himself unable to remit or reduce the fine imposed.[33] The Department was further insulted by the public collection of a penny subscription to cover Edward’s fine. A wealthy benefactor, SJ King, innocently enquired if the Department would agree to Wollaston personally receiving this money. Minister Gillies was outraged: ‘The Minister can only regard this request as an insult and to express his surprise that a gentleman in your position should be guilty of such a proceeding.’ Calmly, King replied that bad laws should be changed: ‘The public having raised the money as a protest against a law that required amending, I sought your permission as the provisions of the Civil Service Act forbid his receiving without your permission.’[34]

There are countless cases of teachers who were disciplined in similar language to that experienced by Wollaston. The Education Department had to appear efficient and the 1872 Act implemented. Discipline had to be exerted and obedience maintained. An unusually articulate and energetic voice, Wollaston was able to use his contacts in local and state newspapers, utilise his social and family networks, and take his case to parliament to seek justice. ‘The whole press of the colony took the matter up and out of twenty six leading articles written on “The Wollaston Case”, twenty four condemned the Minister’s treatment of me.’[35] He obtained legal opinion from David Gaunson MLA, who supported his position. Gaunson was a notorious and colourful figure, an associate of Bent’s and counsel in defence of Ned Kelly in 1880. His opinion was that if rent was paid to the Department for the use of the school building on Sundays, it was constituted as a church at that time. Moreover, on Sundays, Wollaston was ‘untrammelled as a State School teacher’; he was a private person, free to do as he wished.[36] Edward’s cousin, HN Wollaston, then Collector of Customs, was of the same opinion and added that there was no authority to inflict a penalty under Section 12 of the Act.[37] Despite these arguments, the Department and succeeding ministers remained unmoved. Their position as members of government made them responsible for implementing the law and punishing any disobedience on the part of their officers. ‘I had his own admission of the offence before me: what more did I want?’ demanded Gillies to his own Cabinet.[38] Wollaston’s protestations of innocence were always in vain.

It is in the correspondence between King and Gillies that the profound questions that underlay the Wollaston Affair can be seen. King was of the opinion that the 1872 Education Act contained laws that required clarification, if not amendment. Gillies viewed Wollaston’s actions as deliberate and calculated, gross disobedience and a breach of the law. The crux of the disagreement between Gillies and King was the place of religious instruction in schools. ‘That gentlemen who advocate religious instruction being made part of our state school system should have so far shown their sympathy with disobedience to constituted authority and disregard for the law, must, on consideration be rather a matter for deep regret’, wrote Gillies; but for King the whole matter was open to question: ‘… your statement that Mr Wollaston was punished for disobeying his instructions and the law is scarcely accurate, … it is yet more open to doubt (in the opinion of many) whether the law forbids the act, even if the instructions do’.[39]

PROV, VPRS 892/P0, Unit 84, Special Case 894.

It is implausible that Edward insisted on his innocence for so long because he thought he had simply overlooked the key phrase ‘Church service’ in the Campbell letter. He wrote in vain to each incoming Minister of Education for the next forty- two years in an effort to expunge the censure on his record. In 1889 he tried to clear his name with Charles H Pearson, who cited the Wollaston Case during an interview with the London spectator, an interview that was reprinted in a local edition of the Telegraph: ‘I may state, Sir, that, although five years have passed since the occurrence, the sting of unjust blame and punishment remains as keen as ever in my mind’, he wrote.[40] Pearson went through the case papers and came across Wilson Brown’s 1884 letter to Campbell and Campbell’s assertion that he had forwarded the letter to Wollaston. Pearson used this correspondence to accuse Wollaston of dishonesty: ‘You say in a letter of October 9th [1884] that either the words “or Church service” were omitted from the communication you received through the Honorable J. Campbell or they were entirely overlooked.’[41] The Department, he warned, kept facsimile copies of its outward letters. Perhaps Wollaston was ignorant of that fact! ‘It is proved therefore by your own admission that you had received the orders of the Department not to conduct a church service in a state school building.’ As already noted, however, these words did not appear in any direct communication from the Department to Wollaston, at a time when correspondence was flying thick and fast between them. It is entirely possible that the fine wording of a letter to Campbell, which would have appeared a personal one, was overlooked by Wollaston. It was not, after all, addressed to him.

In April 1891 Wollaston wrote to Minister Sargood, again requesting that the fine and censure be removed from his record. A Departmental refusal noted peremptorily that ‘This matter has been dealt with by the Minister’s predecessors in office and he is not disposed to reopen it.’[42] Two months later, the undaunted Edward requested permission from the Department to speak at a public meeting ‘to consider the question of referring the introduction of Scripture teaching in State schools to a plebiscite of the people’. Naturally, he was refused! In March 1892 he requested a public enquiry into his case in order to ’cause the record of fine and censure against me to be erased, not as a favour, but as a clear act of justice’. Again he was refused. His letter of 14 September 1903 was addressed to Minister Sachse. The affair had occurred nine years ago and, as Duncan Gillies was dead, Edward had cause for optimism. ‘That bar to tardy justice being done to me has at last been removed’, he wrote to Sachse, and begged for the erasure of the charges made against him. In 1917 he wrote to Minister Lawson, noting that he was about to retire and asking for the stigma ‘which has so long and so unjustly been attached to me’ to be removed. But Lawson only noted that ‘The question of the remission of the fine has come before several Ministers of Public Instruction who have refused to interfere’. In August 1924, Edward wrote to John Lemmon, a fellow member of the Australian Natives Association, asking for ‘rectification of a wrong which I have borne for 40 years’. Lemmon displayed interest and raised Edward’s hopes when he asked for a meeting. Before this could be held, however, the Minister made a decision based probably on his predecessors’ notes: ‘Cannot re-open the case.’

Perhaps Edward’s most touching letter is to Alexander Peacock, who visited Campbelltown in 1884 as a young reporter and who, in his published article ‘Religious liberty’, expressed sympathy and outrage over the events.[43] By a curious coincidence, Peacock was the Minister of Public Instruction when Edward wrote to him in 1926:

You will remember the general indignation at Mr. Duncan Gillies’ action. In leaving me, as you shook hands, you used the following words: ‘If ever in the future I am in a position to right the great injustice you have suffered, I shall have pleasure in doing it.’

My object in writing is to ask you to have the record of the false charge under which I have lain over forty years, together with the punishment inflicted on me, expunged from the records.

He went on to remind Peacock of their common interests, cricket and the Australian Natives Association. The letter ends on a gentlemanly and courteous note, ‘with kind regards and remembrances of your sixty fifth birthday today …’. The reply was a curt one: ‘Acknowledge and say the Minister is not prepared to reopen this case.’

In 1886 Edward had requested a transfer from Campbelltown to a school where Mary would be close to medical attention. Their second daughter was born in that year and Edward took up a position as second assistant at his old school in MacArthur Street, Ballarat. There is no doubt that his experience at Campbelltown had affected him personally and professionally and delayed any promotion commensurate with his abilities and qualifications. Head teacher Oldham, who previously had befriended and supported him, had been transferred. His position was taken by James Rattray, with whom Edward experienced years of ongoing, bitter conflict. His career stalled, he remained at the level of second assistant, and his teaching and discipline methods came increasingly under the scrutiny of Rattray and the inspectors. To add to his woes, Mary died in January 1904 after years of suffering from uterine carcinoma, leaving him alone with their two young daughters.[44]

After ten years of humiliation, Edward charged his head teacher with ‘having persistently belittled both my intelligence and my teaching ability’ with ‘humiliating interference with my methods’ and with ‘constant limitation of my authority as a class teacher of experience’. The effects were, he claimed, ‘the consequent demoralization of my influence and a lowering of my class results and … making my teaching life absolutely hateful’.[45] The grievance was brought before Inspector Jackson, who formed the opinion that Wollaston was argumentative and contumacious. He thought that Wollaston’s professional shortcomings were due to staleness, as he had been in the same position for twenty-five years. Moreover, Jackson considered that Wollaston’s thoughts, time and energies had been elsewhere: ‘… as a citizen he has expended a considerable portion of his energy in outside work’. Edward’s bitter feud with Rattray and the resulting enquiry into his own teaching practice did not help his professional position. After an extensive and carefully documented investigation, Inspector Jackson delivered a mixed decision. He recommended that Wollaston be transferred immediately to another school as head teacher but that ‘The school should not be in the neighbourhood of Ballarat. In this locality Mr Wollaston has too many engagements outside his school work.[46]

‘Ruffians attempted to carry off the school tent’: a history of state education in Ballarat, Ballarat Times Office, Sovereign Hill, Ballarat, Victoria, 1974, p. 36.

Edward was established in Ballarat. He never completed his university studies but he constructed a rich personal, intellectual and public life. In 1906 he married Florence Hammond, who was born at Poonindie Station in South Australia where his father had once been manager. He travelled regularly to Port Lincoln and later to Adelaide to visit his father, brothers and sisters. He was a member of the Australian Natives Association and the Ballarat cricket team. He had personal contacts in the local press and was a great writer of letters. He taught elocution to children and, like his brother, Tully Cornthwaite Wollaston, he was an author. He wrote and published several histories, biographies and novels. One of these was a semi-autobiographical work, Ulipa: a South Australian story, based on his memories of childhood at Lake Hamilton and his recollections of the people of Port Lincoln.[47] It is Dickensian in tone, a story of sharply observed characters written with laconic humour, wit and empathy. In Ulipa Edward described his view of the individual’s right to deal directly with members of a bureaucracy whose decisions affected his or her life: ‘… many good people look askance upon originality or individuality and treat it as a craze or a taint which must be eradicated, … it would seem that the world is yet far from the wise recognition of individuality as being a special gift of God, worthy of cultivation …’ (p. 99). In later life, when Edward and Florence retired to Railway Parade, Murrumbeena, he called their home ‘Ulipa’.

Photograph Lyn Payne.

In 1907 Edward was promoted to Kirkstall (near Koroit) where he remained as head teacher until 1910. He was then at Nhill until 1913, Casterton for one year and Kyneton where he remained from 1915 until 1918, the year of his retirement. Documents suggest that Edward’s career had no further public rancour, dramatic investigations or bitter confrontations. His marriage to Florence was a long and rewarding union. In 1916 the couple visited Edward’s father in Glenelg and George wrote of his pleasure at seeing them so happy.[48] Edward’s letters to each incoming Minister for Education continued, but these were courteous and gentlemanly, indicated activities and interests they shared, described his story in measured terms and pleaded for removal of Gillies’s judgement against him. Charles Long made an accurate assessment of his friend when he wrote that Wollaston was ‘zealous in Church work’ and ‘wielded the pen of a ready writer’.[49] After Edward’s retirement, he and Florence moved to Ulipa where he busied himself each Tuesday at the Murrumbeena school as one of the religious instruction staff; and every year he was present on Empire Day, Anzac Day and at other celebrations to address the school. There is little doubt he impressed his young audience with his powers of oratory. When Long first saw Wollaston at a recital in Alexandra, he was overcome: ‘On his first appearance at an entertainment … he recited Adam Lindsay Gordon’s “The Sick Stockrider” … On that evening I sat open-eyed and open mouthed. May I say that Gordon’s memory owes something to my hearing that recital when I was about seventeen years old?’[50]

Endnotes

[1] ‘John Ramsden Wollaston (1791-1856)’, Australian dictionary of biography online; DH Wollaston, From now to Domesday with the Wollastons, McAlister & Co, South Australia, 1975, p. 93.

[2] ibid., p. 109; The honorary magistrate (the official organ of the Justices Association), no. 24, July 1910, pp. 307-8; Victorian Index to Births, Deaths & Marriages (BDM), Registration no. 9080.

[3] PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 13718/P4 Teacher Record Books (microfilm copy), Unit 3, Record 5537.

[4] Testimonial, in PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 892/P0 Special Case Files, Unit 84, Special Case 894. The correspondence in Wollaston’s Case File has been drawn on extensively in this article (cited hereafter as Special Case File 894).

[5] Wollaston to Department, PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 640/P0 Central Inward Primary Schools Correspondence, Unit 523, Alexandra State School 912, 18 November 1878.

[6] Mary’s date of birth is noted as 1841 in her Teacher Record, 1844 on her Death Certificate and 1843 on the birth certificate of her daughter Mary Beatrice: BDM Registration no. 187.

[7] PROV, VPRS 13718/P4, Unit 1, Record 35.

[8] ibid.

[9] Wollaston to Department, PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 523, Alexandra State School 912, 2 and 21 December 1877, 12 October 1878.

[10] PROV, VPRS 13718/P4, Records 35 and 5537.

[11] Copy in Special Case File 894.

[12] JT McGowan to Minister, PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 33, Alexandra State School 912, 9 December 1878.

[13] ibid., 11 July 1879.

[14] ibid., 2 September 1879.

[15] Wollaston, ‘A Case for the Minister’, PROV, VPRS 640/P1, Unit 57, Ballarat State School 2022, undated.

[16] Wollaston, ‘Case for the Minister’, op. cit.

[17] BDM Registration nos. 9080 and 38603; GG Wollaston, ‘Diaries of George Gledstanes Wollaston’ (handwritten), State Library of South Australia, Archival Database, PRG 1131/1/2, 8 March 1897.

[18] Wollaston to Department, PROV, VPRS 640/P0, Unit 694, Campbelltown State School 1129, 14 March, 25 March, 8 April and 18 April 1884.

[19] CR Long, ‘History of Alexandra’, Part 1, The Victorian historical magazine, vol. XVII, 1939, p. 176.

[20] Special Case File 894.

[21] GG Wollaston, ‘My trip to Melbourne Exhibition 1880’, in ‘Diaries’, op. cit., PRG 1131/1/1, 6 December 1880.

[22] Wollaston to JN Pritchard, Correspondent, Board of Advice, 30 April 1884, and Department to Wollaston and to Pritchard, 3 May 1884: PROV, VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 796/P0 Outwards Letter Books, Primary Schools, Unit 177, Campbelltown State School 1129.

[23] ibid., Wollaston to Department, 7 May 1884.

[24] ibid., Department to Wollaston, 16 May 1884. See also the Departmental précis of the Wollaston Case in ibid.

[25] Wollaston, ‘Bible reading in state schools’, Ballarat Courier, 14 May 1890, clipping in Special Case File 894.

[26] Wollaston to Minister, 12 March 1892 in Special Case File 894.

[27] G Wilson Brown, Departmental Secretary to J Campbell, VPRS 796/P0, Unit 177, Campbelltown State School 1129, 20 May 1884.

[28] Letter from Wollaston to CN Pearson, Minister of Public Instruction, ibid., in a letter written five years later, 28 September 1889.

[29] Secretary’s Minutes, ibid., 13 September 1884.

[30] Department to Wollaston, ibid., 16 September 1884.

[31] Wollaston to Department, ibid., 18 September 1884 (author’s italics).

[32] Petition to the Minister, Special Case File 894, 18 September 1884.

[33] Department to Petitioners, PROV, VPRS 796/P0, Unit 177, Campbelltown State School 1129, 26 September 1884.

[34] Correspondence between SJ King and Minister Gillies, ibid., October 1884.

[35] Quoted in Wollaston to the Minister of Public Instruction, Special Case File 894, 12 March 1892.

[36] D Gaunson to Wollaston, ibid., 24 August 1901.

[37] Quoted in Wollaston to the Minister of Public Instruction, ibid., 12 March 1892.

[38] Gillies to Cabinet, quoted in Wollaston to A Peacock, ibid., 11 June 1926.

[39] See note 34 above.

[40] Wollaston to CH Pearson, PROV, VPRS 796/P0, Unit 177, Campbelltown State School 1129, 28 September 1889.

[41] Pearson to Wollaston, ibid., 5 October 1889.

[42] Correspondence between Wollaston and the various ministers discussed in this paragraph can be found in Special Case File 894.

[43] A Peacock (‘Special Correspondent’), ‘Religious liberty’, Daily telegraph, October 1884.

[44] BDM Registration no. 187.

[45] Wollaston to Department, PROV, VPRS 892/P0, Unit 84, Special Case 1097, 22 August 1905.

[46] Jackson’s Report, ibid., 13 July 1905.

[47] EG Wollaston, Ulipa: a South Australian story, EE Campbell, Ballarat, 1896. See also Vincent Bostock: a Victorian tale, Fergusson & Mitchell, Melbourne, 1890; On the down grade: a tale of Victorian life in the ’90’s, EE Campbell, Ballarat, 1901; Thomas Carlyle: his life and works: no. 1 of a series of short biographical sketches, G Robertson, Melbourne, 1891.

[48] GG Wollaston, ‘Diaries’, op. cit., PRG 1131/1/4 1916.

[49] Long, ‘History of Alexandra’, p. 176.

[50] ibid.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples