Last updated:

‘"Test A Secure Safeguard of the Children’s Morals": Catholic Child Welfare in Nineteenth-Century Victoria’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 4, 2005. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Jill Barnard.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Catholic orphanages developed as a separate strand of child welfare from Protestant and Government-provided institutions in nineteenth-century Victoria. This paper examines the reasons behind the establishment of these Catholic institutions, the relationship between Catholic charities and the Colonial Government, and the experience of life in Catholic orphanages in the nineteenth century.

On 14 March 1855, a ‘large concourse of people’ gathered to watch the Mayor of Geelong, William Hingston Baylie, lay the foundation stone of the Geelong Orphan Asylum. Although the mood was distinctly celebratory, one of the many speakers struck a sour note. The Marshal, Mr Wright, lamented the complete absence of clergymen on such a Christian occasion.[1] Two days later the Geelong Advertiser published a speedy response to this accusation from Father Patrick Dunne, Catholic Pastor at Geelong. Father Dunne explained that no Catholic clergy had attended the stone-laying ceremony for the orphanage

… not because they were not invited to take part in any religious ceremony … but because we consider that there is not sufficient guarantee that the faith of poor Catholic Orphan Children will be respected, or that they will be educated in this institution in the religion of their sainted forefathers.[2]

Father Dunne acknowledged that there were many worthy citizens on the orphanage committee, but pointed out that ‘there is no Catholic amongst them, and no one but a Catholic can conscientiously guarantee to us the education of Catholic children in their own religion’.[3]

Almost two years to the day after Father Dunne’s letter was published, the foundation stone for St Augustine’s Catholic Orphanage was laid at Newtown, Geelong. Like the Catholic orphanage established earlier in Melbourne, St Augustine’s was a product of the fear expressed by Father Dunne that Protestant-run orphanages would proselytise Catholic children away from their faith. Given that Father Dunne, and most of his brother priests in Victoria, had recently arrived from Ireland, where generations of Catholics had struggled to practise their faith under official oppression, this was possibly not an unreasonable fear. Furthermore, the new colony to which they had come was also showing serious signs of sectarianism.[4] Public debates, played out in the colony’s newspapers, went so far as to argue the merits of allowing Irish Catholic immigrant girls into the colony, with Catholicism depicted as a religion ‘unfavourable to the development of liberty, of safety, of public happiness or progress’.[5] Victoria’s first Catholic Bishop, James Alipius Goold, publicly voiced his concern over the correct religious education for Catholic children when he argued in 1855 that ‘every religious body should have children under their own guardianship’.[6] As Victoria’s Parliament began to debate the merits of State aid for religious education in the 1850s, Goold anxiously set about trying to encourage Irish Religious to migrate to the colony and establish Catholic schools and charitable institutions. The desire to educate Victorian Catholic children in their own religion meant that, despite all the other demands on the resources of the Catholic church in Victoria, four Catholic orphanages had been established in the colony by the early 1860s, compared with three Protestant orphanages in the same period. It also contributed to the Catholic institutions’ divergence from trends in both government welfare policy and the administration of charity in the second half of the nineteenth century and coloured the experience of substitute care for generations of Victorian Catholic children.

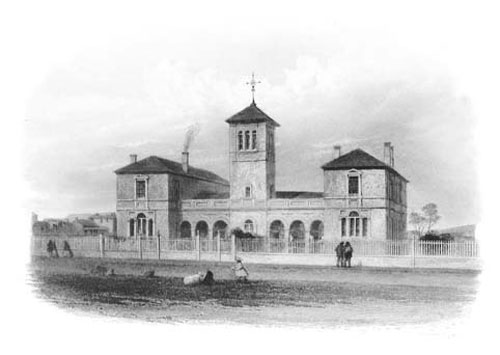

Courtesy MacKillop Family Services Archives. The Catholic Directory of 1858 described the orphanage as ‘like some of the old Irish Abbeys … the sole shelter of many a poor little child, who otherwise might be cast away hopelessly upon a sinful and treacherous world’.

Gold-rush turmoil in Victoria had exacerbated the perception amongst many concerned citizens that Melbourne was in need of an orphan asylum. In the 1840s, church-based charitable groups (both Protestant and Catholic) had made some efforts to accommodate orphaned or abandoned children in the Port Phillip District. The Anglican St James’ Visiting Society had established a shelter for children in 1849 and was soon joined by other Protestant charities to form the committee of what became known as the Melbourne Orphan Asylum.[7] A Catholic lay organisation, the Friendly Brothers, also offered aid to orphans, as well as other destitute individuals, in both Geelong and Melbourne. A few months before Victoria officially achieved separation from New South Wales, the government reserved ten acres of land at Emerald Hill for an orphan asylum. The discovery of gold in Victoria in the same year, however, left the building of the asylum in limbo until late November 1854, when the land was handed over to the committee of the Melbourne Orphan Asylum. By then, immigration, dislocation, death and desertion had greatly added to the number of apparently ‘orphaned’ children in the new colony and the asylum was sorely needed. Not long after the Melbourne Orphan Asylum was granted its site, the Catholic Vicar-General sought land for a Roman Catholic orphanage in the neighbourhood of Melbourne. Two acres were granted, not far from the Protestant Orphanage in Emerald Hill, and the foundation stone for St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage was laid on 8 October 1855.

The driving force behind the establishment of this orphanage was Father Gerald Ward, who had arrived in the colony with Father Dunne in 1850. Early in 1854, Ward had established Victoria’s first branch of the St Vincent de Paul Society, a lay charitable organisation. Soon after, he had become aware of the case of five Collingwood children whose parents had drunk themselves to death. The court had appointed a Presbyterian minister as guardian to the parentless children. But when it became apparent that they had been baptised as Catholics, Father Ward lost no time in successfully applying for guardianship, although the two youngest children, both girls, were eventually allowed by the Supreme Court to remain with a neighbour who had cared for them since their parents’ deaths. The three eldest children, all boys, however, were placed with a ‘respectable’ Catholic woman in Prahran, until they were moved, along with four other children, to the new St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage early in 1857. In August of the same year, the first twelve children moved into St Augustine’s Orphanage.

Under the Care of Religious Staff

Initially the two Catholic orphanages operated in similar modes to their Protestant counterparts. Housing girls and boys in separate dormitories, they were staffed by lay overseers and teachers and managed by committees of management. But even as they opened, Victoria’s first Bishop, James Alipius Goold, was achieving minor success in persuading Religious to come to his aid in Victoria. In 1857, three Irish-born Sisters of Mercy, led by Ursula Frayne, agreed to leave the Mercy Foundation in Western Australia and establish Victoria’s first Religious community. The Sisters took charge of St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage early in 1861. A few months earlier another group of Mercy Sisters, who had travelled directly from Ireland, took charge of the Catholic orphan girls at Geelong. An almost immediate effect of the Sisters’ assuming control was a separation of the sexes – ‘a most desirable regulation’.[8] At Geelong, the orphan girls moved out from under the wing of Daniel O’Driscol, St Augustine’s supervisor, to the convent/boarding school/orphanage that the Sisters of Mercy established at a nearby mansion. At Emerald Hill, where the Board of Management had applied for extra land for a separate girls’ orphanage in the late 1850s, the Sisters set about building St Vincent de Paul’s Girls’ Orphanage in 1863 and began moving the orphan girls into it before it was even completed. Although it was separated from the boys’ orphanage by only a laneway, the girls’ orphanage soon became an enclosed world, with no contact, even for siblings, with residents in the adjacent orphanage. The Sisters of Mercy continued to teach the orphan boys at St Vincent’s until 1874, though they were anxious to hand them over to the care of a male religious order. Finally, Bishop Goold was able to prevail upon the small band of Christian Brothers who had arrived in the colony in 1868 to take charge of St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Orphanage in 1874. In 1878, following the death of long-serving superintendent Daniel O’Driscol, the Christian Brothers also assumed management of St Augustine’s, Newtown, to the relief of the Advocate, the organ of the Catholic hierarchy which had long argued the benefits to Catholic orphaned boys of the Christian Brothers’

mild paternal discipline by which the affections of the child are cultivated, and through which his obedience is won. The children are plastic in the hands of their kind rulers, and are found to readily learn the several trades in which they are instructed.[9]

Increasing Numbers of Catholic Children in Care In the early years of operation, the children at the Geelong orphanage were different from those of St Vincent de Paul. Almost half of the Geelong children had lost both parents and all but one of the children living in the Geelong orphanage in 1860 had at least one parent deceased. By contrast, the high number of children who passed through St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage in the early years (less than half of whom left the orphanage for employment or apprenticeships) suggests that this orphanage was providing temporary relief to widowed or deserted parents who could reclaim their children as circumstances improved.[10] By the late 1860s this seems to have been the pattern at all four Catholic orphanages, with only a small proportion of children having lost both parents. More commonly one parent was deceased, incapacitated or had deserted the family.

|

Increases in residents in Victorian orphanages 1860-1890[11]

|

|||||

| 1860 | 1869 | 1886 | 1890 | 1900 | |

| Total in orphanages | 390 | 978 | 1,151 | 1,170 | 1,088 |

| Percentage of those in care in Catholic orphanages | 35% | 46% | 44% | 45% | 48% |

The numbers of children in both Protestant and Catholic orphanages rose during the 1860s and 1870s. Certainly children formed a greater proportion of the population than they had in the 1840s and 1850s. While many of the earlier immigrants had been single men, now more women were migrating to Victoria and more new families were being formed. But the percentage of Catholic children in the total Victorian orphanage population was out of proportion to the percentage of Catholics in the Victorian population as a whole, which stood at about 20% in the second half of the nineteenth century. By 1869 and from then until the end of the nineteenth century, Catholic children represented almost half of the orphanage population of the colony. The Rev. Matthew Downing, Treasurer of St Augustine’s Orphanage in 1866, suggested one reason for this. Urging larger grants for his institution, he linked the high number of Catholic children in care to the poverty of Victorian Catholics:

It should be borne in mind that the comparative poverty of the Catholic Body and the indigence in many instances of the relatives of orphans preventing them from standing to them ‘in loco parentum’ force into our Orphanages a number of these helpless little ones in excess of the proportion, our position on the Census Roll would entitle to be expected, thus compelling us to provide for a greater number of orphans than falls to the share of the Protestant Asylums though supported by four fifths of the population and who are more prosperous in means.[12]

Downing’s view that Catholic poverty accounted for their over-representation in the orphanages is supported by the number of Catholic children committed to the care of the State as ‘neglected’ children after the Victorian Government passed the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act in 1864. The Act allowed for the establishment of reformatories for juvenile offenders and industrial schools for neglected children. The industrial schools were to be residential institutions where children up to the age of fifteen would be housed, educated in secular and religious subjects, and trained in ‘industrial’ skills appropriate to their station in life. This meant domestic work for the girls and trades for the boys. At the expiry of their term in an industrial school, if their parents did not reclaim them, they would be apprenticed out to work for approved employers. The legislation was motivated by the fear that uncontrolled children would become a menace and later a cost to society. Many were thought to be living in slums, brothels or on the streets, where they could become ‘schooled’ in crime. According to those who supported the legislation, it was inevitable that such children would grow up to fill the colony’s gaols with a dangerous criminal class, instead of becoming the industrious, obedient and sober workers that the new society needed.

The Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act defined neglected children as those found begging or with no place to live, or living in a brothel or with a thief, prostitute or drunkard. Police were given the power to bring these children before the courts to be chargedand committed to industrial schools. Parents could also ask for their children to be committed to such a school if they were ‘uncontrollable’, but they were, in that case, liable to pay for the child’s maintenance.[13] However, one unexpected result of the legislation was that many parents who had difficulty supporting their children sought to have them admitted to industrial schools. The schools were therefore flooded with the children of the poor. In 1864, 653 children were admitted. By the end of 1866, 1,750 children, many of them under six years of age, were living in industrial schools.[14] Although the schools were intended to cater for a different class of children from those who entered orphanages, analysis of the backgrounds of 486 children admitted to industrial schools during 1867 showed that many were in similar circumstances to the orphanage children. Only twenty-nine were the children of prostitutes and nine the children of drunkards. Just under one-half had only one living parent and only a tiny proportion (17) had both parents deceased. One hundred and fifteen of them had been deserted by one parent, but only twelve by both. More than half of them had parents who were unable to support them.[15] By 1873, about half of the total number of children in industrial and reformatory schools were Catholics.[16]

Blurring the Lines Between Neglected Children and Charitable Cases

With the establishment of industrial schools, the orphanages were expected to no longer accept children who had two living parents and only take ‘true orphans’, such as those with no parents or without a father to provide for them. The Catholic Church established two industrial schools for girls. A small one, St Joseph’s, was located at Our Lady’s Orphanage in Geelong. A larger establishment was founded by the Good Shepherd Sisters at Abbotsford. But the other Catholic orphanages continued to accept children with two living parents or with working fathers, to the annoyance of the Government-appointed Inspector of Charities, who argued that ‘if [the children’s] natural guardians are unable to take care of them, they come within the scope of the Neglected Children’s Act’.[17] The Inspector pressured the Catholic orphanage managers to refuse to accept such children or, at the very least, to make parents pay something toward their maintenance. Mother Sebastian Whyte, who had ultimate responsibility for St Vincent de Paul’s Girls’ Orphanage, explained her reluctance to comply with this policy in benevolent terms:

It is true there are children in the Institution having one parent, and in some cases both parents living, but who are more destitute than many orphans in the strict sense of the word. The cases being as follows, Father dead, mother bedridden, father dead, mother obliged to go to service, father dead, mother dying, mother dead, father without anyone to mind his children while he is working, mother dead, father in hospital, father insane, mother dying, mother drinks, father unable to mind his children, father whereabouts unknown, mother destitute.[18]

The fear, on the part of authorities, that parents would take advantage of charitable institutions encouraged a harsh attitude even to those with a genuine need for assistance to raise their children. At the 1870 Royal Commission on Charitable Institutions, the superintendent of the Melbourne Orphan Asylum testified that the rules of the institution were, that ‘before any destitute mother, shall have any child in the orphanage she must have three left with her after the one taken before any one be taken in’. Fathers could only place children in the Orphan Asylum if they were ‘sick, or under very special circumstances’.[19] The Catholic orphanages appear to have taken a more humane approach. Sister Ursula Frayne, on behalf of the St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage, testified that a widow would be ‘relieved’ of all of her children if she were ‘in poor circumstances’, while a working father would be relieved of the care of his children if he paid something toward their upkeep.[20] Evidence suggests that, until badgered into it by the Inspector of Charities in the 1880s, Catholic orphanage managers were not always diligent about ensuring that parents were made to pay for the maintenance of their children in the orphanage.

Protecting Children

Religious managers of the Catholic orphanages were also placed under pressure over the matter of keeping older children, above the age of thirteen, in the orphanages when their place was really out at service (for girls) or as apprenticed farm labourers (for boys). The Sisters of Mercy, in particular, attracted such criticism. In Melbourne, the Sisters established an ‘industrial training school’ for older orphan girls at their convent and school (now called Academy) in Fitzroy. Here older girls were ‘trained’ for domestic service by acting as servants at the boarding school. The Inspector of Charities strongly objected to government funding being expended on the maintenance of these girls and waged a long battle to have this funding suspended. The Sisters responded that they had found the system of sending young, untrained girls out to domestic situations to be

in every respect defective, the children were found to be as useless as we know they are when first they join the training class, with the additional discomfort of trying too much the patience of strangers – the poor children were beaten and otherwise maltreated in several cases they absconded from their employers. Some of them found their way back to the Orphanage, while many drifted away from one place to another until they were heard of no more. All this was the result of children being sent amongst strangers, unexperienced in the world’s ways and ignorant of domestic service, which for want of proper appliances they could not be taught at the Orphanage.[21]

Resistance to Boarding Out

Keeping the girls in the institution, albeit as unpaid servants, was the Sisters’ way of delaying their exposure to the dangers of domestic service until they were trained and, presumably, old enough to withstand any ill-treatment or seduction at the hands of employers. But while this, and other humane policies adopted by the Catholic orphanages, helped to swell their resident numbers, it is also true that Catholic authorities considered that their orphanages, particularly those under the supervision of Religious staff, were the safest way to guarantee that Catholic children in colonial Victoria would be educated ‘in the religion of their sainted forefathers’.[22] This concern, first voiced when the issue of the abolition of State aid to religion was being discussed in the 1850s, became even more of a threat after the Education Act of 1872, which cut off government financial assistance to denominational schools. In the same year as the Act was passed, a Royal Commission on Penal and Prison Discipline had concluded that large institutions did not provide appropriate care for children and recommended that Victoria’s industrial schools be replaced by foster care or ‘boarding-out’for State wards. Foster families were to be paid a small sum to take children in. Local visiting committees would inspect these private homes and children were to be sent to the nearest State school. The State-run industrial schools were rapidly emptied and even the Melbourne Orphan Asylum adopted the ‘boarding-out’ system from 1876, boarding out about three-quarters of its charges by 1888.[23]

The Inspector of Charities tried to encourage the Catholic orphanages to adopt the boarding-out system as well. Commenting on a request for funds for additions to the buildings at St Vincent’s Girls’ Orphanage in 1887, Inspector Captain Evans ventured ‘to express an opinion that the erection of additional accommodation for the orphans should be discouraged rather than encouraged. All modern ideas are in favour of boarding out. In NSW the Government has refused to assist in supporting children retained in Orphan asylums …’.[24]

Evans did have some success in convincing the Christian Brothers at Emerald Hill and Geelong to board out some of their younger boys, but, on the whole, the Catholic orphanages strenuously resisted the move. The Catholic hierarchy opposed boarding-out primarily because children would be sent to the State school nearest to their foster home. There was also anxiety that foster parents might have unscrupulous motives for taking children in. Brother Patrick Canice Butler, Superior at St Augustine’s, explained to the 1892 Royal Commissioners that his orphanage had not

adopted the boarding-out system except in the case of very young children. After careful examination and consideration, I would say that persons suitable and fit to take charge of such children do not, as a rule, care to take them; whereas, those who might not be considered the most suitable are anxious to get them, perhaps as a means of livelihood for themselves or as cheap little servants.[25]

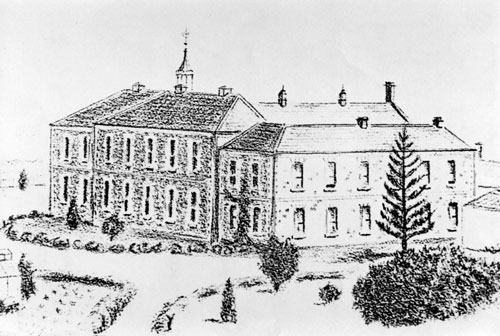

The two-storey extension on the right was added in 1885. The orphanage buildings now form part of St Joseph’s College, Newtown. Courtesy MacKillop Family Services Archives.

In 1884, putting the case against boarding-out, the Advocate argued that the cleanliness and healthiness of Catholic orphanages made them far superior to many private homes. Furthermore, there was less opportunity for orphanage children to miss out on schooling because of truancy, parental illness, neglect or inadequate clothing. But the main advantage that the orphanages offered was that they provided a ‘secure safeguard’ of the children’s morals. ‘The nuns alone can give the children such assistance in this direction as Catholics desire and in the nuns alone can Catholic parents place their confidence.’[26] Whether it was this point, or the fact that they resented other families looking after their children, some Catholic parents obviously agreed. Of the 23 young boys boarded out from St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Orphanage between 1888 and 1890, seven were reclaimed by their parents soon after the Brothers had placed them in foster homes.[27]

The Fabric of Life in the Catholic Orphanages

How did the Religious staff manage to provide this ‘secure safeguard’ of the orphanage children’s religion and morals in the nineteenth century? Education in the Catholic orphanages was intended to train the children to be virtuous, hard-working and pious. Religious education was a high priority, especially for the girls. It would train them to act ‘faithfully and habitually on solid principles of virtue’.[28] The boys’ religious training, including ‘practices usually taught by good Catholic mothers to their children’, was also meant to stand them in good stead as they went out alone into the world.[29] Clergymen visited the orphanages to instruct and prepare children for their first communion and confirmation, but daily life was also interspersed with prayers, and lessons were ‘infused’ with religion, as they were in all Catholic schools. In Ireland, the Christian Brothers had developed a series of ‘school books’ that had gained wide acceptance by educationalists beyond the Brothers’ own schools. The same books were introduced by the Christian Brothers to Victoria and presumably used by them in their orphanage schools. After the passage of the 1872 Education Act, the Sisters of Mercy, at Emerald Hill, also began using the Christian Brothers’ school books.[30] This ensured a thoroughly Irish and Catholic tone to the material presented to the children in reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography and singing.

Moreover, the children were kept busy. Although the Sisters of Mercy at Emerald Hill vowed that the children had three hours of recreation, with which ‘nothing is suffered to interfere’, it is difficult to see where they fitted this in. The boys spent their evenings mending boots, while the girls made and mended clothes and knitted stockings. In addition, the boys cultivated the garden and worked at ‘such domestic works as are suitable to them’ and the girls were taught to ‘wash, cook, etc as far as their strength permits’.[31] Older children, both girls and boys, were also required to give ‘all the assistance in their power, out of school hours’ to helping staff with domestic duties and caring for the younger children.[32]

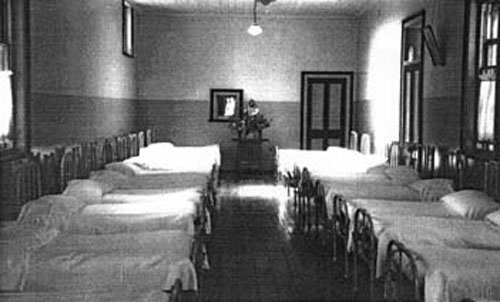

Physical or emotional ties among the children or with their carers were discouraged. The Sisters of Mercy followed the Irish-published manual, Guide for the Religious. While the Guide advised them to be ‘maternal’ and ‘kindly’ to the children, it frowned on emotional ties, for ‘the habit of such foolish attachments weakens the mind, strengthens a dangerous tendency and accustoms the heart to receive impressions which may be dangerous at a future time’.[33] Similarly, the Christian Brothers were forbidden to touch the children under the noli me tangere rule. But, while relationships were distant, there was constant supervision of the children. An 1882 circular letter from the Christian Brothers’ Superior-General in Ireland emphasised the need to watch carefully over boys in both schools and institutions in order to ‘maintain a healthy state of morality’. Brothers were advised to keep boys under surveillance in the playground and especially in the ‘water-closets’ (toilets) where ‘much harm may be done, and sin not infrequently committed… if necessary precautions be not taken and if wholesome discipline be not strictly enforced’.[34] Likewise, a staff member was encouraged to sleep in each dormitory to prevent the dangers of masturbation or homosexual activity at night.

The strict separation of the sexes into different institutions, and into dormitories segregated according to age, meant that children were frequently separated from siblings. Parents were not overly encouraged to visit their children. St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage Annual Report for 1870 advertised that parents were able to visit the orphanage on only four Sundays throughout the year. Nor was there any guarantee that children would be reunited with siblings once they had gone out into the world to work, as there was scant exchange of information between the managers of the Catholic orphanages, and ‘the ties of relationship between children [might be] still further severed by their being sent to parts of the colony far distant from each other’.[35] To the Inspector of Charities, the segregation of the sexes was hardest on the younger boys in all-male orphanages, without the maternal care of the Sisters or even female siblings. Though they seemed happy, he felt it was a shame that they were growing up without ‘female influence and oversight’. ‘Big boys are but rough companions for infants’, he commented.[36]

Rigid timetables and cramped conditions left little room for personal space. The managers of the institutions consistently argued for building grants on the basis of overcrowding and their complaints were borne out by the reports issued after the annual visits of the Government Inspector of Charities. The Inspector found that in all of the orphanages dormitory space was inadequate, while, in some, bedsteads were actually touching. At times, children were obliged to share beds or sleep on the floor.[37] New facilities did not necessarily improve the amount of space allotted to each child, for as soon as extra space was provided, more children arrived to fill it. A new wing added to St Augustine’s Orphanage in the 1860s included a dining-room on the ground floor, while the upper storey was entirely taken up by a dormitory ‘sixty feet by twenty-five feet’ (18 metres x 7.5 metres). Thirty beds were arranged around the walls of this dormitory, with thirty ‘block tin hand basins’ occupying the centre of the room.[38]

There is scant documentation of how children viewed their experience of orphanage life in the nineteenth century. In the early days, some showed their disapproval by ‘absconding’, but as high fences and walls began to surround the orphanage buildings (in the case of St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’, complete with a topping of broken glass), the opportunities for escape became limited. Because the children were educated within the institutions and also participated in most of their religious rituals within the orphanage grounds, there was little opportunity to break the monotony of daily life through outings. The boys at least enjoyed some opportunities to move beyond the walls. At Geelong, they participated in Catholic picnic and sports days, while the boys from St Vincent’s Orphanage enjoyed the occasional treat, such as a trip down Port Phillip Bay offered by benefactors. Some of the boys also experienced the benefit of belonging to brass bands, which the Christian Brothers instituted at both orphanages in the early 1880s. But there was little respite from life behind the walls for the girls of either St Vincent’s or Our Lady’s. And, though inspectors’ reports usually recorded that the children seemed happy and healthy enough, Royal Commissioners examining charitable institutions in 1870 noted that ‘the most rigid economy is apparent throughout the Catholic Orphanages, perhaps to a somewhat undesirable extent’.[39]

Discrepancies in Funding the Catholic and Protestant Institutions

The necessity for ‘rigid economy’ was partly due, as Father Downing had suggested, to the relative poverty of nineteenth-century Victorian Catholics. In comparison with the Protestant orphanages, the Catholic institutions struggled to attract donations and bequests. Between 1860 and 1869, for instance, while the Melbourne Orphan Asylum was able to attract £15,400 in subscriptions and other ‘locally-raised’ funds, the neighbouring Catholic orphanages managed only £9,491. At Geelong, private contributions were a little more evenly matched. The Geelong Orphan Asylum raised £5,541 for this period, St Augustine’s, £4,981 and Our Lady’s Orphanage only £2,399. The amount raised privately by each orphanage affected the government charity grant they received. The law allowed a charitable vote of two-thirds for every one-third raised by the institutions. However, even allowing for the matching of funds, the Catholic orphanages, particularly at Geelong, were hard done by. While both the Protestant orphanages received slightly more than two-thirds of their income from government sources in the 1860s, more than a third of the two Geelong Catholic orphanages’ income came from non-government sources. The 1870 Royal Commission found that the 1869 grant per child to each of these orphanages was 2s 6d, while that to the Protestant Orphanage was 5s 9d, and concluded that ‘the Catholic Orphanages of St Augustine and Our Lady had not received the support from the State, in the shape of annual grants, in proportion to other institutions of a similar character’.[40] An 1862 Royal Commission had suggested that government nominees sit on the committees of management of charitable institutionsin order for them to qualify for their charities vote. But once Religious took over the management of Catholic orphanages there were no committees of management and perhaps this is one reason why they fared relatively poorly until Inspectors of Charities were introduced to assess each institution on an annual basis. The Inspector nagged at the orphanage managers to attempt to collect support money from parents who could afford to pay something towards their children’s maintenance. But, at the same time, government funding for building programmes at the institutions was reduced.

Courtesy MacKillop Family Services Archives.

For some of the Catholic orphanages, particularly those for boys, support from the Catholic community started to increase in the latter decades of the nineteenth century as benefactors began to bequeath small amounts to the institutions in their wills and subscription lists broadened. But Our Lady’s Orphanage continued to struggle until the early decades of the twentieth century, when a small group of Geelong Catholics attempted to raise funds for the Orphanage, and when a change of name to St Catherine’s differentiated it from the girls’ college on the same convent site. By that time other Catholic children’s welfare institutions – garnering no government funding – had been established. With the passing of legislation to introduce a Charities Board in 1922, fairer funding models, which generally lifted the standards of care in institutions, also came into being. And, in the 1930s, when ‘boarding-out’ for State wards began to decline and the Victorian Government had to turn to the denominational homes to accept Wards of the State, the proportion of funds from government sources began to increase. But by then hard work and education had produced a broader Catholic middle class and, under the influence of Archbishop Daniel Mannix, a network of parish social clubs, sodalities, friendly societies and support groups had developed. As Victorian Catholics adopted an ‘inturned and isolationist posture’[41] in the decades after World War I, the Catholic charities reaped some benefits. These included greater voluntary financial support through fund-raising events and philanthropy, and also a wider public awareness of the lot of children in Catholic institutions. Voluntary holiday host programmes, sewing circles and special ‘treats’, such as Christmas parties and picnics, began to offer more relief from the blandness of life behind orphanage walls.

While the strengthening of a sense of Catholic community in the inter-war period helped to improve the lives of children in Catholic institutions, it probably also contributed to an expansion and consolidation of the Catholic system as a separate strand of child welfare in Victoria. Father Dunne’s concerns that Catholic children be educated in the faith of their forefathers were, if anything, accepted even more widely by the Catholic community, guided by the charismatic Archbishop Daniel Mannix in the extremely sectarian climate of his time.

Endnotes

[1] D Jaggs with C Jaggs, Advancing this good work: a history of Glastonbury Child and Family Services, the organisation, Geelong, 1988, p. 6.

[2] Geelong Advertiser,16 March 1855, p. 2.

[3] ibid.

[4] Geoffrey Serle argues that ‘suspicion and fear of Roman Catholicism and prejudice against the Irish were deep-rooted in almost every British migrant’ in Victoria in the early 1850s. The Golden Age: a history of the colony of Victoria 1851-1861, Melbourne University Press, 1968, p. 63.

[5] Argus, quoted in P O’Farrell, The Catholic church and community in Australia, Nelson, West Melbourne, 1977, p. 110.

[6] Argus, 8 October 1855, p. 5.

[7] S Bignell, ‘Orphans and destitute children in Victoria up to 1864’, Victorian Historical Magazine, vol. 44, nos. 1 & 2, February-May 1973.

[8] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 104, File 4834.

[9] Advocate, 27 July 1872, pp. 5-6.

[10] Information about children in the orphanages is derived from early registers of St Augustine’s Orphanage and annual reports of St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage, located at MacKillop Family Services Heritage and Information Service Archives.

[11] Figures derived from ‘Statistics on charitable institutions in the colony’ in the various reports in the Votes and proceedingsof the Victorian Legislative Assembly.

[12] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 349, File 4969.

[13] Jaggs, Advancing this good work, pp. 25-6.

[14] ‘Industrial Schools. Report of the Inspector, for the year 1866’, Votes and proceedings. Papers presented to both Houses of Parliament … Session 1867, Legislative Assembly, vol. 4, pp. 941-51 (949).

[15] ‘Industrial Schools. Report of the Inspector, for the year 1867’, Votes and proceedings … Session 1868, vol. 3, pp. 873-882 (879).

[16] Advocate, 22 August 1874, p. 10.

[17] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 1281, File 11267.

[18] Superior, Convent of Mercy to Under Treasurer, 10 April 1889. Mercy Congregation Centre Archives, Fairfield, Victoria, Australia.

[19] ‘Charitable institutions. Report of the Royal Commission’, Votes and proceedings … Session 1871, vol. 2, p. 57 (p. 33 of the report).

[20] ’Report of the Commissioners appointed to enquire into the municipalities and the charitable institutions in Victoria’, Votes and proceedings … Session 1862-3, vol. 4, p. 569.

[21] Mother Ursula Frayne to Under Treasurer, 28 January 1882, (copy), Mercy Congregation Centre Archives.

[22] Geelong Advertiser, 16 March 1855, p. 2.

[23] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 1229, File 10934.

[24] PROV, VPRS 1207, Unit 11336, File 7314.

[25] ‘Royal Commission on charitable institutions’, Votes and proceedings. Papers presented to Parliament … Session 1892-3, vol. 4, p. 744.

[26] Advocate, 29 March 1884, p. 9.

[27] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 1313, File 6959.

[28] Guide for the Religious called Sisters of Mercy, London, 1888, p. 19.

[29] Circular Letters of Superiors-General of the Brothers of the Christian Schools of Ireland, the Brothers, Dublin, 1882, p. 92.

[30] K Twigg, Shelter for the children: a history of St Vincent de Paul Child and Family Service, 1854-1997, Sisters of Mercy, Melbourne, 2000, p. 42.

[31] Annual Report of the St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage Emerald Hill, the Orphanage, Melbourne, 1868, p. 18.

[32] Report of the St Vincent de Paul’s Orphanage Emerald Hill for the year 1870, the Orphanage, Melbourne, 1871, p. 19.

[33] Guide for the Religious, p. 20.

[34] Circular Letters of Superior-General, p. 97.

[35] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 1313, File 6959.

[36] PROV, 1207/P0, Unit 919, File 9379 and Unit 912, File 7567.

[37] PROV, VPRS 1207/P0, Unit 335, File 1672.

[38] Advocate, 16 January 1869, p. 7.

[39] ‘Charitable institutions. Report of the Royal Commission’, Votes and proceedings … Session 1871, vol. 2, p. xiii.

[40] ibid.

[41] O’Farrell, The Catholic church and community in Australia, p. 352.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples