Transcript Episode 5: Pentridge prison escape

Duration 30 min

From the podcast series ‘Look History in the Eye’

Written, produced and presented by Tara Oldfield and Public Record Office Victoria

Music and sound design by Jack Palmer

Guests: Crime writer Susanna Lobez, with additional voice acting by Jason Oldfield and Asa Letourneau

Susanna Lobez

There really are three ways to undergo a prison sentence. The soft way. Which is where the prisoner obeys all the rules and works off their time as quickly as they can. Then there’s the hard way. In which case they cause the authorities as much grief and aggravation as they possibly can and become known as a troublesome prisoner. And of course the third way is to escape.

Tara Oldfield

It’s 3 o’clock on a sunny winter’s Saturday afternoon, 27 August 1955. At Coburg’s Pentridge Prison, 76 prisoners are taking part in a football finals match in the farm area of the gaol. Only three unarmed warders oversee the match of Pentridge’s hardest criminals including violent thieves Peter Leslie Dawson, Kevin Arnold McGarry, John Henry Taylor, Raymond Kevin Morrison and murderer William O’Meally. What could possibly go wrong?

By 1955 countless prisoners had already escaped Pentridge Prison since it first opened more than 100 years prior.

The first to escape Pentridge was Scottish Bushranger Frank Gardiner in 1851. The Rutherglen Highway Robber John Henry Sparks was never heard from again after his escape in 1901. Kenneth Raymond Jones was nicknamed “Boots” after escaping shoeless in 1940, using strategically placed shoes to trick guards into believing he was still in his cell. He was on the run for two weeks, sparking a massive manhunt, while twelve years later, Kevin Joiner, didn’t make it out alive. Frequent escapee Maxwell Carl Skinner once called Pentridge the easiest gaol to escape from.

Skinner (Jason Oldfield)

“All you need is plenty of guts and the ability to keep running.”

Tara Oldfield

You’re listening to the Podcast “Look History in the Eye” produced by Public Record Office Victoria, the archive of the state government of Victoria. Where over one hundred kilometres of public records about Victoria’s past are carefully preserved in climate controlled vaults. We meet the people who dig into those boxes, look history in the eye, and bother to wonder… why.

Records related to Pentridge Prison escapes can be found in the state archival collection. One such record is the Report of the Board of Inquiry into the escape of five prisoners from Her Majesty’s Gaol, Pentridge, on Saturday the 27th day of August 1955.

My name is Tara Oldfield, I’m the communications officer at Public Record Office Victoria, and those who read our blog regularly will know that I have quite the interest in Victorian true crime. It was this interest that led me to look at the Board of Inquiry report into the 1955 Pentridge escape. But I certainly wasn’t the first to delve into its pages.

Susanna Lobez is a Melbourne crime writer who has co-authored 13 non-fiction books with James Morton including Dangerous to Know, Gangland Robbers and Bent: Australia’s Crooked Cops. In 2018 they released Gangland the Great Escapes which tells the true tales of escapes and escapees who have driven, walked, pedalled, swum and even sailed away from custody. Pentridge is one of the prisoners Susanna researched and wrote about for this book. And in understanding the story of the 1955 escape, it pays to revisit the history of the gaol.

Susanna Lobez

Well Pentridge was built, and I use the term loosely built, in 1851, now at that stage Victoria wasn’t even Victoria it was Port Phillip and what they said was originally there was a stockade which makes me think of a kind of you know a wooden fort. It was surrounded by hundreds of acres of land which had a prison farm where they used to grow their vegetables and have their chickens. And also a quarry where they used to break rocks and presumably earn some money for the prison.

Within months there 48 escapees who got out from outside the stockade, so obviously the farm wasn’t very secure. In 1851 in March there were 17 inmates who were working on the farm and they all bunched together and rushed the warders and escaped. Nine of them were fairly soon after recaptured but interestingly the bushranger Frank Gardiner was one of them, I think he used a couple of names but we knew him best as Frank Gardiner, and he stayed out and on the run until 1854, when I believe he was found in NSW so he managed to get clean away.

Then in the August that year, 1851, again, there was a 31 man work team out at the quarry breaking rocks, 23 of them made a dash for it. One in that instance was shot dead and after that clearly security was called for and was stepped up.

One of the stories I really love about early Pentridge was a few years later 1854 in May that year there was a fellow called Edward Ryder who was doing several years as a horse thief because of course that was one of the common crimes around Port Phillip and Victoria in those days. He actually was working at the Governor’s house, Governor Price. Governor Price had a wife. And I don’t know whether Edward Ryder was working in the garden or as a maintenance man or a cleaner or I don’t know what but one day he dressed completely up in Mrs Price’s frock, her full dress, her handbag, her parasol, even a rather dramatic face veil that he found, and he walked genteelly out past all the warders who were saluting as he went, he was never seen again in Victoria, so he also got clean away.

James Walker was really recognised as one of the most formidable men in the post world war 2 era in the Melbourne underworld. In 1953 James Walker, “Pretty Boy”, was sentenced to death and uh he had shot someone in the stomach with a shot gun. So, he actually asked for the death penalty to be administered because he didn’t really wanna go back to Pentridge So, in the May of 1954 Walker had reported sick and was told to stay in his cell which was what the normal treatment was. He was taken to see the warder in charge a bit later and when the escorting officer left the room, as I say he’d managed to get hold of a gun and some bullets, he pulled out his gun and said “Look I’m really sorry I have to do this but I’m a desperate man”. He had six bullets in the gun, he said “five I can use on you and I’ll still have one left for myself.” So he knew he was sort of going to blaze his way out and probably die in the process. So there were others who heard shots being fired and a whole bunch of other warders came running and when it became clear that he was going to have to shoot a warder, Walker shot himself in the head instead. Now, he was taken to the Royal Melbourne Hospital where he died soon after. But he left behind a whole lot of written allegations of widespread corruption, brutality and cruelty that were occurring in Pentridge and they were published in the Argus at the time.

Tara Oldfield

It was in the shadow of Walker’s beyond the grave revelations about Pentridge that the 1955 saga began. On the 27th of August 1955, Peter Leslie Dawson, Kevin Arnold McGarry, William O’Meally, Raymond Kevin Morrison and John Henry Taylor were among more than 70 prisoners participating in and watching a footy final at the prison.

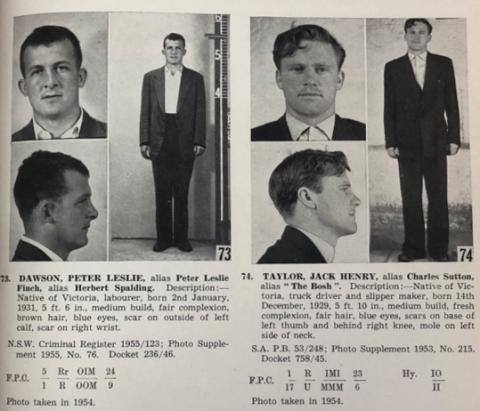

Described by police as “dangerous in a corner”, blue-eyed 24-year-old Peter Leslie Dawson was a skilled housebreaker serving a five and a half year prison sentence. 23-year-old Kevin Arnold McGarry was serving nine years for two charges of robbery under arms. He’d been shot in the leg by a guard, during a disturbance at the gaol, just a year earlier. Also involved in that disturbance was McGarry’s partner in crime, five foot ten, 26-year-old John Henry Taylor. Taylor was serving a ten year sentence for three charges of robbery under arms. He was once described by a reporter for The Argus as being a “cool, calm dare-devil driver” with a “shock of fair hair hanging over his forehead” and “never without a gun.” 25-year-old Raymond Kevin Morrison, according to the Inquiry report, was serving fifteen months for illegally using motor cars.

Susanna Lobez

Now it’s interesting because if you’ve only got ten months or fifteen months why would you run the risk of going for an escape you know, you try and do your time. You do your time you keep your head down, you don’t get any additional months or years or sentences, and you get out.

Tara Oldfield

Not in this instance. By far the hardest of the criminals was 28-year-old William O’Meally, a convicted murderer with a long history of violent crime. He was serving life imprisonment for killing a police constable, George Howell, in 1952. Headlines at the time called O’Meally “wicked and dangerous”. In court, he claimed his innocence.

Susanna Lobez

So William O’Meally was the one who had the most to achieve by escaping on this fateful Saturday. The prison authorities had decided that although earlier the prisoners had used a slightly small yard within the big bluestone walls of the prison as a football stadium, football arena, they had decided this particular year they would use an arena which was outside the prison walls on the adjacent farm. You know there was acres and acres and acres of farm and so they’d arranged this football match. Interestingly whenever authorities or caring sharing social workers decide that maybe the prisoners should have some recreation or some amenity or something to occupy their brains or their bodies, sport or theatre, invariably escapes or escape attempts happened.

Tara Oldfield

Sure enough, weeks earlier William O’Meally had boasted to frequent escapee Maxwell Skinner...

O'Meally (Asa Letourneau)

I'll be out in two weeks and as free as you.

Tara Oldfield

O’Meally’s presence on the football list at the time was questioned by the Chief Warder of B Division. But the Governor overruled him. Players were decided based on good conduct and industry, not based on security. The prisoner should be given a chance. Interestingly both O’Meally as well as Taylor had previously been caught plotting escapes from Pentridge. Yet it came to be, O’Meally and Taylor were among those playing football with the inmates from Pentridge’s B and C divisions that day, supervised only by three unarmed gaol warders. The match was played without incident. Whether B or C Division won is unclear. What is clear is what happened at the game’s conclusion. Guns lay in waiting in the bushes of the yard. At the time of the inquiry it was unknown who’d smuggled the guns in, years later though a safebreaker named Patrick Shiels confessed to lowering the ladder from the guard tower and placing the guns under a mattress in a shed near the footy ground. The escapees were supposed to go that Saturday but couldn't find the guns. So he had to sneak back in to get a message to O’Meally to let him know where the guns were hidden. Then it was on.

According to the Board of Inquiry report:

“At the conclusion of the match, at 3.15pm, the three warders in attendance, who were unarmed, were suddenly confronted and menaced, at a range of about 9 feet, by the prisoners Dawson and Taylor, who were then armed with a rifle and shot-gun, respectively. The three other escapees joined in, and two of the warders, named Elliott and Walton, were seized by the arms, and hurried, with threats, to an unoccupied control tower, known as No. 13 Post, on the outer wall, about 170 yards away. There the five prisoners climbed up a rope affixed to the wall, which controls the ladder to the post, and dropped to the other side, taking the firearms with them, and leaving the two warders inside. While all this was taking place, shots were fired from the three nearest occupied posts, but without apparent effect. The third warder, Mr Scoberg, who had been left with the other 71 prisoners, after sounding the alarm on his whistle, returned them to the gaol without further trouble.”

It’s a wonder more prisoners didn’t seize the opportunity to make their own escape, riding the coat tails of the five who planned it. Susanna says many attempts often involved guns, but others didn’t...

Susanna Lobez

Pentridge was added to over the years and eventually we got the edifice which was the big blue stone walls and towers that we all remember from pictures of Pentridge when it was operating as a gaol. But there were still plenty of attempts and many of them involved the old, the old trick of making a kind of grappling hook out of knotted sheets and a broom so you’d make a rope of knotted sheets and tie a broom on the end and that kind of worked as a bit of a grappling hook to throw over the walls. Other inmates who had escape on their minds would avail themselves of hacksaw blades and these were hidden in the most incredible places, sometimes within the room, behind a mirror, they were known to have come into the prison between the soles of a person’s shoes – this was before metal detector days – and so in between the two layers of sole the leather and the larse they would squeeze a hacksaw blade. I even heard of one where the hacksaw blade was concealed in a tube of sweet and condensed milk and, for later use, you know, so all kinds of tricks they had. One of the things that becomes apparent when you look at the history of escapes from Pentridge is that it’s always good to try for a weekend or a public holiday. One example is Ryan and Walker, the famous Ronald Ryan who was the last man hanged in Victoria, they waited until the 19th of December when the warders were having a Christmas party. Always good to wait until you know there’s fewer guards on duty. The other thing to do is behave well for a few months because you don’t want to be on the Governor’s watch list or don’t allow him any recreation or any time outside or any access to amenities or functions such as football or theatre.

Tara Oldfield

As was the case in 1955. Maxwell Skinner once said of Pentridge that the prospective escapee’s biggest ally lies in what is supposed to be the gaols best link – it’s warders. He said they were underpaid, not properly disciplined, and fighting amongst themselves. Prisoners knew that the warders’ guns and other equipment were antiquated and if they made a run for it and kept dodging there is a better than even chance that they wouldn’t be hit.

According to Susanna it was football and theatre events, among other prison activities, that often provided the perfect opportunity for escape.

Susanna Lobez

It’s quite interesting that sometimes they had things like football matches or theatre events that the prisoners could participate in or could watch, and often they occurred on weekends so, there were always fewer guards on the weekend because the prison authorities didn’t want to have to pay overtime to the prison officers so you pretty much knew there was going to be fewer people watching out. The other thing about the prison farm was outside the main block of the bluestone towers at Pentridge, was operative well into the 50s and 60s and that was the occasion of many people who probably shouldn’t have been allowed out to the prison farm outside the big high walls, but they were for whatever reason, and that gave them escape opportunities.

Of course one of the problems in prison is that you can’t really trust anybody. And so you might be friends with your cell mate or you might have a bunch of fellows you feel close to. But it’s very hard to keep secrets in prison, and if one person hears of a story of an escape and someone else might want to do it and someone else might want to curry favour with the guards and so dob them in, that’s happened many many times where someone’s got wind of an escape and dobbed them into the guards so they might look for kinder treatment or a better go with the magistrate next time they’re in court. So very hard to keep a secret with five people in on the job. Very commonly it’s two or three, because you sometimes need a bit of a hand and you’ve got one guy up on the wall handing down a rope or a bunch of sheets to the guy whose down low. Often they had help on the outside so they’d arrange through visitors to have a car somewhere or whatever. But two or three is probably the most common number. There were a few lone foxes who managed to escape completely by themselves. And there were also events where there were several prisoners who were, you know, stormed the barricades as it were.

Tara Oldfield

As was the case in this instance - with Dawson, McGarry, Taylor, Morrison and William O’Meally getting away. But of course escaping the confines of the prison is only the first in a number of hurdles for escapees to overcome. O’Meally found that out the hard way. He was caught within only a few hours along with McGarry and Morrison. They were chased down by two warders by car and then foot, and recaptured with the assistance of a few brave civilians. Said The Mirror:

“Leader of the sensational, five-man “crash out” from Pentridge prison in Melbourne last week-end, convicted murderer William John O’Meally is perhaps the most dangerous criminal in Australia. O’Meally is a killer, a basher, a thug – but he is also tall and good-looking, quietly spoken, well-mannered, well-dressed, a plausible liar, a shrewd planner, a slick and intelligent thief. In prison for life he still menaces the society which condemned him. The scourge of Pentridge he is feared and hated by warders and prisoners alike.”

But back to Pentridge he and his two comrades went. Then there were two. Dawson and Taylor proved more difficult for police to recapture. According to the 1955 Police Gazette entry for the 1st of September:

“After escaping from Pentridge Gaol, Coburg on 27th August 1955, they held a man at gunpoint and took his Austin panel van to facilitate their getaway. The panel van was abandoned at Berwick. A 1954 Holden sedan, two-tone green, registered No GFE 456, which has not yet been recovered was then stolen from Berwick. By breaking into the Royal Mail Hotel at Whittlesea, they were able to provide themselves with food and clothing, and, when leaving, assured themselves a means of transport by taking the licensee’s motor car. This in turn was abandoned at Carlton North and was found to contain blood-stained prison garb. It is believed Dawson has been wounded. These men are dangerous, determined criminals known to be armed and will undoubtedly make a desperate stand to avoid recapture.”

It was later determined, the two were able to remain at large, in part, due to the help of a woman named Lillian Jean Boundy. The papers described her as the broken hearted lover of a man still serving time at Pentridge. She took the escapees in, fed them, bathed a bullet wound Dawson had acquired during the escape, and assisted them in checking into hotels. Her hospitality didn’t save the men from recapture however, as the lure of a Collingwood jeweller proved armed robber Taylor’s undoing. After robbing the store, Taylor crashed the black Holden he was driving before being recaptured by police who’d been chasing him. Though Dawson had held up the jewellery store with Taylor, he couldn’t be found by police at first, as they searched the area extensively. But by the next day, he too was found seeking refuge at a house in Richmond.

The 1955 inquiry found many failures on the part of Pentridge management contributed to this particular escape.

Susanna Lobez

The board of inquiry report which looked at the 1955 escape of these five blokes was very interesting because it certainly attacked the choice by the Governor and the senior warders of allowing 76 prisoners outside the walls of Pentridge into that farm area, the 60 acres or so of farm, which housed this much bigger oval with plenty of places where weapons could be concealed, and later retrieved by escapees. It was a number of prisoners, many prisoners from B division which was considered to hold a number of very dangerous criminals including O’Meally. O’Meally was in for life, he was a security risk, he proved in the end to be a multiple escapee. Why he was let out, not necessarily to play football but to be a spectator, was clearly the subject of some scrutiny by the inquiry. There were only a couple of guards who were supervising. They were, two of them were guards who were assigned to the young offenders area, which were probably less experienced younger guards. None of the guards that escorted the football players or the football spectators from the walls of the prison to the farm were armed. Because obviously it was feared that prisoners, 76 to 3, could take the guns off the guards and shoot them. And shoot their way out. However there were guard posts, only two of which were manned, and it was found that the guns and ammunition which were the weapons up in the guard towers – two I think were manned, one wasn’t – they were hundreds of metres away from the football oval. And it was found afterwards, after some examining, that the guns were old decrepit, out of date and couldn’t have shot even 100 metres accurately from the watch towers. Another interesting thing was that the poor old guards, you know, if they were lucky, they’d had an hour and a half practicing to use a gun and maybe firing five shots as part of their training. That wasn’t considered adequate by the board and there were recommendations: better guns, better ammunition that wasn’t kind of all powdery and old, and more training of guards in using the guns should be instituted in the future. And that this one particular guard post should always have been manned. Further the Governor who sort of rubber stamped this whole endeavour of 76 prisoners coming out of the walls of the prison to enjoy a day of footy, he was really more interested in helping the prisoner morale with a bit of recreation rather than being concerned about dangerous prisoners who were going out with unarmed guards. So it was decided by the inquiry board that once he retired, which you got the feeling they hoped it was going to be fairly soon, that they would install a very modern new younger Governor who had his wits about him and who was aware of who the most dangerous criminals were that were in his prison and not to let them out.

Tara Oldfield

The inquiry said: “I feel bound to find the Governor displayed an improper lack of sense of responsibility in the approving of prisoners to attend the football matches, and that this was the principal single factor leading to the escape.”

Recommendations were made to address the failings including that the outer wall of the farm area be made more secure, that sporting activities be confined to the Gaol proper, and that more effective rifles and better training be applied, to name a few.

The report said: “That an escape such as this from Pentridge, which is properly regarded as the State’s “maximum security” prison, should have been possible must of necessity cause uneasiness in the public mind, particularly when, as was the case, there had been three other successful escapes from the same prison within the preceding ten months. The cause of those escapes was not a subject for this inquiry, but it must be agreed that the evidence given at this inquiry disclosed a lack of precautions which, to the criminal mind, made this escape quite an easy matter.”

Yet escape didn’t get any harder.

Susanna Lobez

O’Meally and Taylor teamed up again a couple of years later to attempt an escape they were armed with a point 38 automatic hand gun and they ran through the front gates of the gaol. There was a chief officer who tried to stop them and he was shot in the thigh which broke his femur. O’Meally then took the firearm from Taylor and was literally involved in a gun battle with the warders. They got out, they got out into Coburg and who knows which main road they were heading for but they were recaptured literally within 20 minutes of getting out of the gaol. Now, when they went back to court to be dealt with for that subsequent breakout they were told by Mr Justice Hudson that they were both clearly beyond hope of reform. He said simply to sentence you to a term of further term of imprisonment would be to impose a totally inadequate form of punishment and provide no real deterrent against further attacks of a similar character. They were both sentenced to ten years more gaol, in this case, O’Meally, it didn’t mean much to him because he already had life. But both were also sentenced, and remember we’re in 1957, to 12 strokes of the cat of nine tails – the whip with many heads. Which was to be delivered in one session. And I think that was the first flogging to be handed out at Pentridge since 1943. And O’Meally appealed the flogging, he couldn’t appeal his life sentence, but he appealed the flogging however both the Supreme Court and the High Court upheld the order. And the flogging was delivered on the first of April 1958, April Fools Day for the flogging, and it turns out Taylor and O’Meally were the last men flogged in Victoria with the cat of nine tails. O’Meally said you know it opened up his rib cage and he had wounds and he wasn’t given proper medical attention but he would wouldn’t he. Well after that O’Meally was sent off to break rocks. I’m not sure if he was out in the quarry under very strict supervision or if he had somewhere within the walls of the prison, he was moved again because he assaulted a warder and broke that warders false teeth, so he must have clocked him in the mouth, and he was also put in solitary confinement at one stage. He later, he went onto serve 27 years, and wasn’t released on parole until 1979 when the court accepted a recommendation of the parole board, the adult parole board, interestingly he was the longest serving prisoner in Victoria and had done most of his time in Pentridge. He was last heard of in Queensland and it’s thought he might have died there in the mid 90s.

Tara Oldfield

One has to wonder, what makes a prisoner more likely to escape, and if determined enough, what measures would stop him?

Susanna Lobez

The book that James Morton and I wrote called Gangland the Great Escapes, we researched hundreds of escapees and escapes all over Australia. You know you get the feeling that escapees, especially if they’re really taking a risk when there are warders with guns, they are taking a risk of injury and death, they tend to have longish sentences. If you’ve only got 6 months, just pull your head in and do your time as quietly as you can. Don’t raise your head above the parapet. But if you’ve got a longer sentence then it’s more likely that you’re going to be inclined to make a break. Ronald Ryan who escaped with Walker in 1965 – part of the reason I think he escaped when you read some of the material about him, was because he’d been trying to do well. He’d been working in the woollen mills in Pentridge and then he’d been sent to a country prison where a particular prison governor was very enlightened and had taken a bit of an interest in Ronald. He was on the path to improvement. But then when he went back to court to be dealt with for a subsequent matter the judge imposed what Ryan saw and what judges sometimes refer to as a crushing sentence. So that would always give, that bitterness, that feeling that you’ve been crushed, would give a prisoner a bit of motivation to try and escape. Often they’re risk takers, they’re gamblers, some of them have nerves of steel. So they weren’t stupid many of them. They had a good strategy a good plan and sometimes they made it, sometimes they didn’t.

Tara Oldfield

Thank you to Susanna Lobez for her time and expertise, and to Jason Oldfield and Asa Letourneau for voicing the parts of the criminals within this podcast. The records used within this podcast can be found on our website at prov.vic.gov.au.

Sources

Susanna Lobez and James Morton, Gangland: The Great Escapes, 2018

The Argus, Melbourne, Vic. Monday 29 August 1955

The Argus, Melbourne, Vic. Wednesday 7 September 1955

The Argus, Melbourne, Vic. Thursday 8 September 1955

The Argus, Melbourne, Vic. Thursday 22 September 1955

Victoria Police Gazette, 1955

VPRS 30 P0 Kenneth Raymond Jones Criminal Trial Brief, 1941

VPRS 2965 P0 Board of Inquiry into the Escape of Five Prisoners from H.M. Gaol, Pentridge on Saturday 27 August 1955